|

Size: 40315

Comment:

|

← Revision 88 as of 2017-05-06 11:11:36 ⇥

Size: 40283

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 176: | Line 176: |

| * Aroch I., Targan N., Gancz. A.Y. (2013). A Novel Modified Semi-direct Method for Total Leukocyte Count in Birds. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine 68(2). | * Aroch I.; Targan N.; Gancz. A.Y. (2013). A Novel Modified Semi-direct Method for Total Leukocyte Count in Birds. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine 68(2). |

| Line 179: | Line 179: |

| * Chan, Y., Tsai, M., Huang, D., Zheng, Z., & Hung, K. (2010). Leukocyte Nucleus Segmentation and Nucleus Lobe Counting. BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1), 558. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-558 * Decaro, N., Campolo, M., Lorusso, A., Desario, C., Mari, V., Colaianni, M. L., . . . Buonavoglia, C. (2008). Experimental infection of dogs with a novel strain of canine coronavirus causing systemic disease and lymphopenia. Veterinary Microbiology, 128(3-4), 253-260. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.008 * Gyorffy, A., & Ronai, Z. (2011). Standard data, supplement for the physiology practical course. University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, 4. |

* Chan, Y.; Tsai, M.; Huang, D.; Zheng, Z.; Hung, K. (2010). Leukocyte Nucleus Segmentation and Nucleus Lobe Counting. BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1), 558. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-558 * Decaro, N.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, A.; Desario, C.; Mari, V.; Colaianni, M. L.; Buonavoglia, C. (2008). Experimental infection of dogs with a novel strain of canine coronavirus causing systemic disease and lymphopenia. Veterinary Microbiology, 128(3-4), 253-260. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.008 * Gyorffy, A.; Ronai, Z. (2011). Standard data, supplement for the physiology practical course. University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, 4. |

| Line 183: | Line 183: |

| * Honda, T., Uehara, T., Matsumoto, G., Arai, S., & Sugano, M. (2016). Neutrophil left shift and white blood cell count as markers of bacterial infection. Clinica Chimica Acta, 457, 46-53. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2016.03.017 * Jones, M., & Allison, R. W. (2007). Evaluation of the Ruminant Complete Blood Cell Count. Vet Clin Food Anim, 23, 377-402. * Lilliehöök, I., Gunnarsson, L., Zakrisson, G., & Tvedten, H. (2000). Diseases associated with pronounced eosinophilia: a study of 105 dogs in Sweden. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 41(6), 248-253. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2000.tb03934.x |

* Honda, T.; Uehara, T.; Matsumoto, G.; Arai, S.; Sugano, M. (2016). Neutrophil left shift and white blood cell count as markers of bacterial infection. Clinica Chimica Acta, 457, 46-53. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2016.03.017 * Jones, M.; Allison, R. W. (2007). Evaluation of the Ruminant Complete Blood Cell Count. Vet Clin Food Anim, 23, 377-402. * Lilliehöök, I.; Gunnarsson, L.; Zakrisson, G.; Tvedten, H. (2000). Diseases associated with pronounced eosinophilia: a study of 105 dogs in Sweden. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 41(6), 248-253. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2000.tb03934.x |

| Line 187: | Line 187: |

| * Moore, D. M., Zimmerman, K., & Smith, S. A. (2015). Hematological Assessment in Pet Rabbits. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 35(3), 617-627. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.05.010 * Peterson, M. E., Nesbitt, G. H., & Schaer, M. (1981). Diagnosis and Management of Concurrent Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperadrenocorticism in Thirty Dogs. American Veterinary Medical Association,1(178), 1st ser., 66-69. |

* Moore, D. M.; Zimmerman, K.; Smith, S. A. (2015). Hematological Assessment in Pet Rabbits. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 35(3), 617-627. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.05.010 * Peterson, M. E.; Nesbitt, G. H.; Schaer, M. (1981). Diagnosis and Management of Concurrent Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperadrenocorticism in Thirty Dogs. American Veterinary Medical Association,1(178), 1st ser., 66-69. |

| Line 190: | Line 190: |

| * Ramoji, A., Neugebauer, U., Bocklitz, T., Foerster, M., Kiehntopf, M., Bauer, M., & Popp, J. (2012). Toward a Spectroscopic Hemogram: Raman Spectroscopic Differentiation of the Two Most Abundant Leukocytes from Peripheral Blood. Analytical Chemistry,84(12), 5335-5342. doi:10.1021/ac3007363 * Schnelle, A. N., & Barger, A. M. (2012). Neutropenia in Dogs and Cats: Causes and Consequences. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 42(1), 111-122. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.09.008 * Serrano, B., Almeria, C., García-Ispierto, I., Yániz, J. L., Abdelfattah-Hassan, A., López-Gatius, F. (2011). Peripheral white blood cell counts throughout pregnancy in non-aborting Neospora caninum-seronegative and seropositive high-producing dairy cows in a Holstein Friesian herd. Res Vet Sci ,(90), 3rd ser., 457-462. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.019. * Tavares-Dias, M., Oliveira-Júnior, A. A., & Marcon, J. L. (2008). Methodological limitations of counting total leukocytes and thrombocytes in reptiles (Amazon turtle, Podocnemis expansa): an analysis and discussion. Acta Amazonica,38(2), 351-356. |

* Ramoji, A.; Neugebauer, U.; Bocklitz, T.; Foerster, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Bauer, M.; Popp, J. (2012). Toward a Spectroscopic Hemogram: Raman Spectroscopic Differentiation of the Two Most Abundant Leukocytes from Peripheral Blood. Analytical Chemistry,84(12), 5335-5342. doi:10.1021/ac3007363 * Schnelle, A. N.; Barger, A. M. (2012). Neutropenia in Dogs and Cats: Causes and Consequences. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 42(1), 111-122. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.09.008 * Serrano, B.; Almeria, C.; García-Ispierto, I.; Yániz, J. L.; Abdelfattah-Hassan, A.; López-Gatius, F. (2011). Peripheral white blood cell counts throughout pregnancy in non-aborting Neospora caninum-seronegative and seropositive high-producing dairy cows in a Holstein Friesian herd. Res Vet Sci ,(90), 3rd ser., 457-462. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.019. * Tavares-Dias, M.; Oliveira-Júnior, A. A.; Marcon, J. L. (2008). Methodological limitations of counting total leukocytes and thrombocytes in reptiles (Amazon turtle, Podocnemis expansa): an analysis and discussion. Acta Amazonica,38(2), 351-356. |

| Line 196: | Line 196: |

| * Weiss, D. J., & Wardrop, K. J. (Eds.). (2010). Schalm's veterinary hematology (6th ed.). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell. | * Weiss, D. J.; Wardrop, K. J. (Eds.). (2010). Schalm's veterinary hematology (6th ed.). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell. |

Impacts and Significance of White Blood Cell Counts in lymphocytic and neutrophilic species

Contents

Introduction

White blood cells, also called leukocytes generally have a significant role in the body. They act as indicators of defect and diseases and are found throughout the bloodstream and tissues of of lymphocytic species and neutrophilic species, where they represent either the innate or adaptive immune system. The white blood cell count is a test used to measure the number of leukocytes in the body. It can be performed using a variety of different methods and equipment. A total WBC count above or below the normal range can be a useful indicator of underlying physiological or pathological conditions providing an important diagnosis in both human and veterinary medicine.

Blood Cells

Blood cells are cells that are mainly found in the blood, and are produced via hematopoiesis. While the liquid component of blood, plasma, makes up 55% of the blood, blood cells make up 45% , and can be categorized into 3 different groups erythrocytes, thrombocytes, and leukocytes. Leukocytes are white blood cells that are in charge of immunological response, and can be differentiated into granulocytes and agranulocytes (Maton, 1994).

Granulocytes are characterized by the presence of granules in their cytoplasm. The most abundant type of granulocytes are neutrophil granulocytes, then low numbers of eosinophil granulocytes, basophil granulocytes, and mast cells granulocytes. Granulocytes are also known as polymorphonuclear leukocytes for the varying shape of their nucleus.

Agranulocytes, which only contain a single nucleus in their cells, have the varying name mononuclear leukocytes. In comparision to granulocytes, they’re characterized by the absence of granules in the cytoplasm. There are two types of agranulocytes: lymphocytes and monocytes.

Neutrophil Granulocytes

|

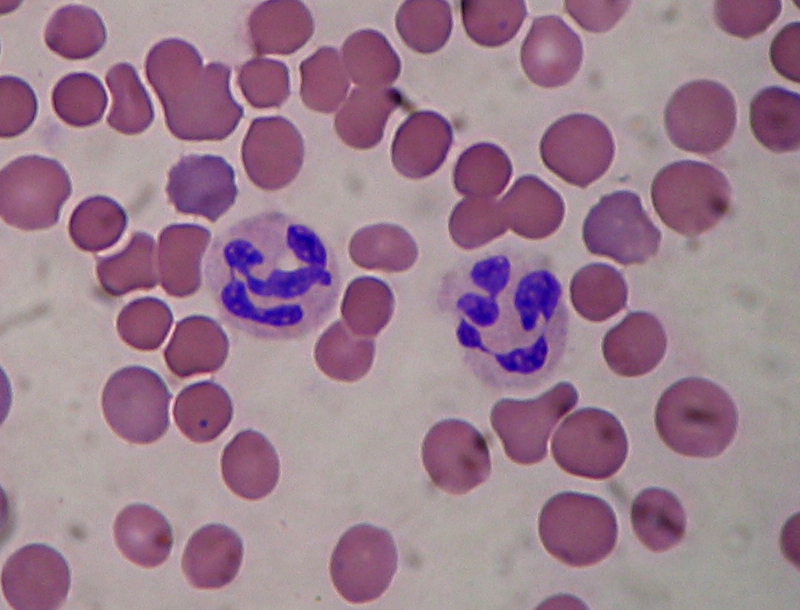

Normal neutrophil morphology is similar in common domestic mammalian species. The chromatin of the nucleus is condensed and segmented and stains blue to purple. Nuclear lobes may be joined, but generally there is simply a narrowing of the nucleus between lobes without true filament formation (Harvey, 2005).

Band neutrophils, which are the most common type of immature neutrophil seen in blood, is one stage less mature compared to segmented neutrophils. They can be distinguished from matures by the shape of their nucleus, lacking the clear segmentation (Chan et al, 2010).

Heterophils are the most common leukocyte in avian blood and are analogous with mammalian neutrophils, however their nuclei aren't as lobulated (Harvey, 2005).

Lymphocytes

Lymphocyte morphology can be characterized by its pale blue color of the cytoplasm and their nuclei are usually round or oval, allowing some slight indentation. Most of the lymphocytes that circulate in healthy dogs, cats, camelids and horses are small cells that have round nuclei with dense chromatin and a small rim of light blue cytoplasm. The chromatin is so dense because it is mostly heterochromatin (the cell is not actively transcribing DNA) (Havey, 2005).

|

WBC Counts

White Blood Cell count (WBC count) is an important subset of the complete blood count (CBC), as the number of leukocytes in the blood is often an indicator of disease (Ramoji et al, 2012). The WBC count is the total number of leukocytes in a given volume of blood. This count can be performed either manually or by automated cell counters.

The differential white blood cell count measures the percentage of each leukocyte subtype in an individual’s blood. It is performed by counting and identifying 200 consecutive leukocytes in a single drop of blood.

The absolute count for each leukocyte subtype can then be calculated by multiplying the differential by the total white blood cell count (Walker et al, 1990).

Total white blood cell counts in adult domestic animals (× 10*9 /l) (Gyorffy and Ronai, 2016)

Species |

Lymphocytes |

Neutrophil |

Eosinophil |

Basophil |

Monocyte |

horse |

1.5-7.0 |

2-8 |

0-1 |

0-2.9 |

0-1.5 |

cattle |

2.5-7.5 |

0.6-4.0 |

0-2.4 |

0-0.2 |

0-0.8 |

sheep |

2-9 |

0.7-6.0 |

0-1 |

0-0.3 |

0-0.8 |

goat |

2-9 |

1.2-7.2 |

0-0.7 |

0-0.2 |

0-0.6 |

swine |

4-24 |

3-20 |

0.5-2.4 |

0-0.4 |

0.2-22 |

dog |

3-11 |

3-11 |

0.1-0.3 |

0-0.2 |

0.2-1.5 |

cat |

1.5-7.0 |

3-12 |

0-1.5 |

0-0.2 |

0-1.5 |

rabbit |

6 |

3 (heterophil) |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

Domestic fowl |

7-17.5 |

3-6 (heterophil) |

0-1 |

0-0.1 |

0.1-2 |

According to the ratio of lymphocytes and neutrophil granulocytes in blood circulation, species can be categorized into two groups: Lymphocytic and neutrophilic species, where lymphocytic species yield higher amounts of lymphocytes compared to neutrophil granulocytes and vice versa for neutrophilic species. Species such as cattle, swine, sheep, and domestic fowl are considered to be lymphocytic species, whereas neutrophilic species are the horse, dog, and cat.

Impacts and Significance of WBC Counts

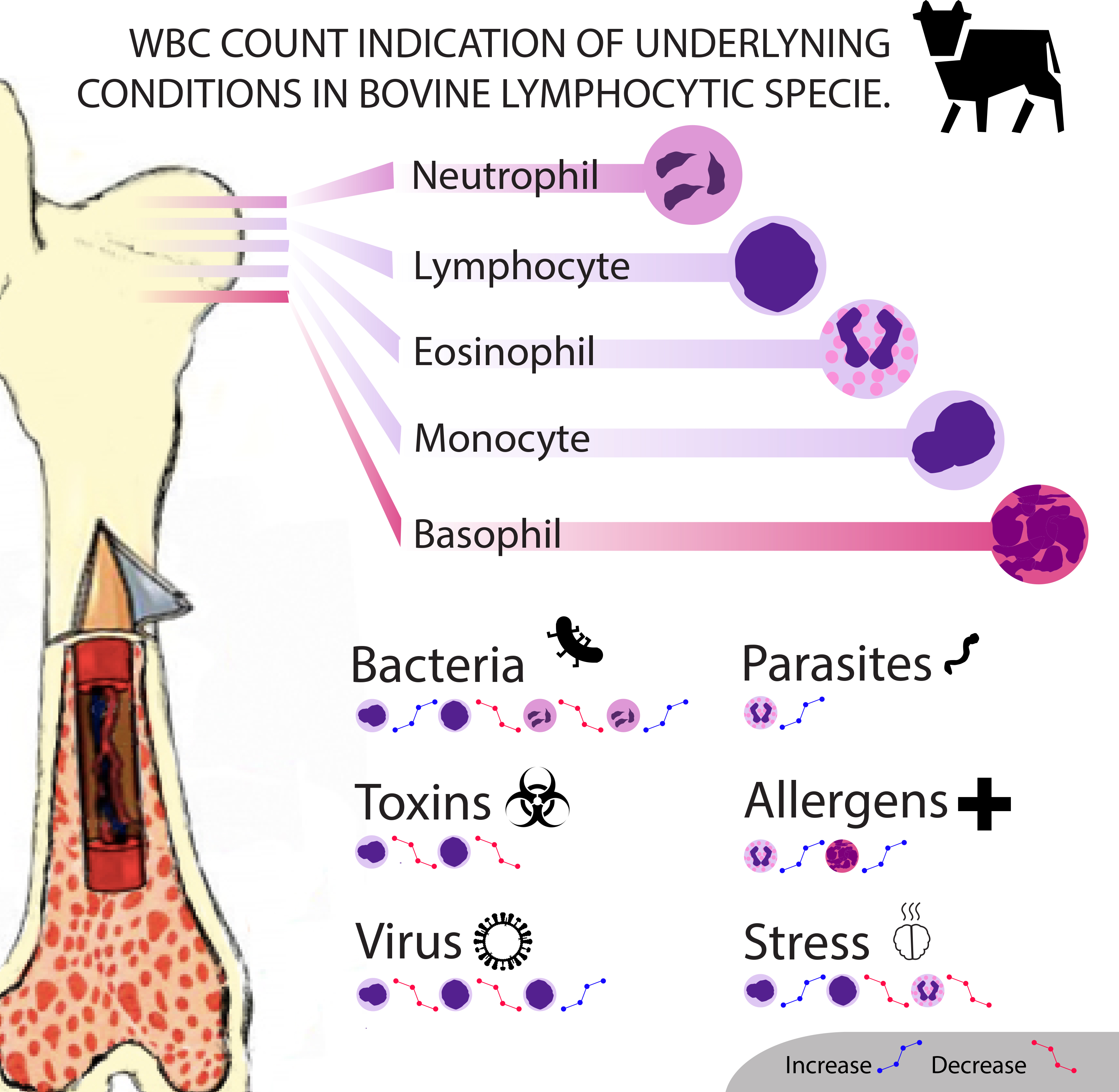

Changes in white blood cell counts can indicate many alternations occurring within the body. The changes can be either physiological or pathological, and will cause different results in lymphocytic and neutrophilic species . Physiological causes include age, body mass, time or season, and stress. Meanwhile infections from viruses, parasites, and bacteria are considered as pathological causes, along with the effect of toxins.

Species-Specific Causes

Lymphocytic Species

Bos taurus

|

Physiological Causes:

Age: Calves typically have lower numbers of eosinophils, lymphocytes with dominant neutrophil concentrations; however as they grow up lymphocytes becomes dominant during adulthood (Jones and Allision, 2007).

Time, Season: In cattle species during the warm seasons, blood sample tests prove rising concentrations of neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes counts compared to the opposite effects of cold seasons (Serrano et al, 2011).

Stress: stress manifests through a common decrease in lymphocytes and eosinophils concentration but is also associated with a slight monocyte increase (Jones and Allison, 2007).

Pregnancy: The white blood cell count profile on healthy dairy cows is affected by factors such as physiological stress, breed, age, postpartum and pregnancy status. Days 90-150 of gestation have an increasing effect on neutrophil and lymphocyte counts decreasing towards the end. High levels of milk production result in a decrease in leukocytes counts throughout pregnancy while lower levels exhibit decreases on eosinophil counts during day 90 of pregnancy. It is also important to mention that twin pregnancy is considered as a decreasing factor for leukocyte and lymphocyte counts on day 180 of gestation. Basophils are observed in very small numbers during pregnancy, which make them not relevant for practical studies (Serrano et al, 2011).

Pathological Causes:

Bacteria Infection: Acute severe inflammatory disease of bacterial origin including Salmonella infections and inflammation of organs (uterus, breast, peritoneum and lung) can affect neutrophil production causing neutropenia (associated to lymphopenia) as well as neutrophilia but mostly related to tissue injury of non inflammatory conditions (Jones and Allison, 2007).

Virus Infection: In cattle, persistent lymphocytosis can be observed by those that are infected with bovine leukemia virus (BLV) (Harvey, 2005)

Parasites: Low levels of neutrophil counts and high levels of monocytes during day 180 of pregnancy are related to Neospora-seropositive cows. Neospora caninum is a parasite where infected non-aborting cows show increased levels of leukocyte during the second half of gestation due to immune response. Also protozoan parasites and a variety of Helminths are common for increasing eosinophil population.

Toxin: Severe lymphopenia may be seen with corticosteroid administration or endotoxemia as well as low monocyte levels (Jones and Allison, 2007).

Other: In cattle, basophils may be present in higher numbers in clinically normal calves than adults and function in allergic and inflammatory processes (Serrano et al, 2011).

Ovis aries

|

Physiological Causes:

Age: Goats exhibit equal or slightly increased neutrophil concentration compared to lymphocytes when they are older than 3 years of age (Jones and Allison, 2007).

Stress: Sheep exhibit neutrophilia due to environmental stress and excitement causing epinephrine release (Polizopoulou, 2010).

Pregnancy: In pregnant sheep and goats, they also experience leukocytosis with neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and also mild eosinopenia noticeable at the time of parturition. In sheep however these changes are resolved by the 14th day post-partum.

Pathological Causes:

Virus Infection: Though uncommon, chronic viral infections can lead to an increased number of lymphocytes which can be seen in sheep with autoimmune disorders.

Parasites: Normally sheep suffering from parasitic diseases can be in the state of eosinophilia.

Toxins: In sheep endogenous or exogenous corticosteroid actions, acute infections or endotoxemia are the most common causes of low concentrations of lymphocytes.

Others: Sheep species manifest low neutrophils concentration due to inflammation or sepsis (Polizopoulou, 2010).

Oryctolagus cuniculus

|

Physiological Causes:

Time, Season: In the morning circulating lymphocytes are found in high level concentrations differing from the low neutrophil levels, but during late afternoon lymphocyte concentrations decrease and neutrophils increase.

Stress: Chronic stress manifest a general leukopenia (Moore et al, 2015).

Pathological Causes:

Bacteria Infection: A slight concentration increase in eosinophils and neutrophils can be seen in chronic parasitism and acute infections of pyogenic bacteria (associated with lymphopenia). Although, overwhelming acute or chronic bacterial infections exhibit neutropenia.

Virus Infection: Viruses can cause a higher production of circulating lymphocytes, lymphocytosis, suppressing neutrophils.

Toxins: Chronic exogenous steroid administration and endotoxemia causes general decrease in lymphocyte and neutrophil concentrations (Moore et al, 2015).

Neutrophilic Species

Carnivora

Physiological Causes:

Stress: Physical and psychological factors such as car transportation, introduction to a new environment and kennelling, are reasons for an increase in neutrophils counts, showing symptoms like: diarrhoea, vomiting, coughing, sneezing and skin problems. An experiment was carried out to determine the effect of acute stress in dogs and it was shown that rescue dogs, mostly females, are more sensitive for longer periods (Bodnariu, 2008). Commonly stress increases cortisol levels in dogs and other species. Eosinopenia characterized as “stress leukogram” together with a general development of neutrophilia, lymphopenia and monocytosis, is associated with secondary diseases such as diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperadrenocorticism. The stress leukogram is moderate mostly by glucocorticoids release rather than epinephrine release due to excitement (Peterson et al, 1980; Barger, 2003).

Pathological Causes:

Bacteria Infection: In dogs, bacterial infections such as rickettsial infections, along with fungal and protozoal infections cause reactive monocytosis. Specifically, dogs with bacterial endocarditis, chronic mycobacteriosis, and ehrlichiosis have been reported with monocytosis. Monocytosis with necrotic disorders can show to symptoms such as: hemorrhage, hemolysis, malignant neoplasia, infarction, and trauma. However, neutrophilia is more of a reliable indication of infection (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010; Honda et al 2016).

Parasites: In dogs temporary eosinophilia is associated with large mucous membrane surfaces in organs such as the gut, lung and skin and persistent cases are related to specific diseases like parasitic infections in countries with warm climates, pulmonary infiltrates, hypoadrenocorticism and flea hypersensitivity (Lilliehook et al, 2000).

Virus Infection: One major virus known for causing lymphopenia along with other systemic disease is the canine coronavirus in dogs and after the viral infection, acute lymphopenia occurred in all infected dogs, with values dropping below 60% of the initial counts (Decaro et al, 2008). In the case of feline species, virus such as the feline retrovirus, feline leukemia virus (FeLV), and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) are notable in cats suffering with neutrophilia. Also Canine parvovirus (CPV), feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) are two well- known pathogens characterized by suppression of neutrophil count. A report describes how cats infected with Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) medicated with Griseofulvin, show a decrease in neutrophil concentration but in healthy cats it does not have the same effect (Shnelle and Barger, 2012).

Toxins: Suppression of neutrophil cells particularly in cat species can be caused by chemotherapy drugs such as Vincristine and Azathioprine treatment, but dogs may be affected as well. In dogs the most frequent cause of monocytosis is due to excess endogenous or exogenous corticosteroids.

Other: The genetic disorder Cyclic Neutropenia, or grey collie syndrome is a disorder primarily affecting the grey collie. It is marked by severe cyclic neutropenia and affected dogs exhibit a diluted grey coat color along with frequent infections as a result of their neutropenia (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010).

Equus caballus

Physiological Causes:

Pregnancy: In mares total WBC count is decreased but still within the normal reference range during pregnancy.

Age: Directly after birth healthy foals will show a neutrophil count that often exceeds the normal adult count. However premature foals will have a significantly lower neutrophil count. In those that survive the count will improve to reach normal levels within a few hours. Foals will also show general lymphocytosis and an absence of eosinophils. By 3 months, the leukocyte count will be the same as that of the adult (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010).

Pathological

Parasites: Heavy intestinal parasite burdens in horses can result in eosinophilia.

Bacteria Infection: Prolonged exposure to endotoxins produced by bacteria will result in neutropenia, if this exposure is terminated then a rebound neutrophilia will occur (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010).

Non species-specific

Parvovirus infections can be a cause of monocytopenia in many species, not just canine and feline as mentioned before. However, the number of monocytes typically seen in normal blood is very low, and therefore little importance is usually attached to monocytopenia. Monocytopenia is rare as an isolated finding.

Allergic diseases and parasitism, both endo- and ectoparasites, are most often responsible for basophilia. Since basophils are important players for protective immunity, basophilia is seen accompanied with eosinophilia associated with Immunoglobulin E mediated disorder. Ectoparasites such as fleas and ticks, gastrointestinal parasites such as nematodes, and vascular parasites have been documented in causing basophilia. If it is not accompanied with eosinophilia it may signify that corticosteroids have lowered eosinophil levels more than those of basophils (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010).

Relevance to Veterinary Medicine

Interpreting WBC Counts: It is very important in veterinary medicine for veterinarians to realise that the normal absolute and differential WBCs are not static numbers but that they lie within a range. As we have shown above changes outside of the normal reference ranges occur not only due to pathological factors but can also change due to physiological causes during the animal’s lifetime (e.g. during pregnancy). This is a very important fact for practitioners to keep in mind when interpreting blood results and so they must consider and rule out these normal, physiological causes before further investigation into possible pathological causes.

WBC Counting Method: When measuring the number of leukocytes present, it should be estimated to assure that number present on the slide is consistent with the total leukocyte count measured. The total leukocyte count in blood may be estimated by determining the average number of leukocytes present per field and multiplying by 100 to 150 in case of 100X magnification. If a 20X objective is used, the total leukocyte count may be estimated by multiplying the average number of leukocytes per field by 400 to 600. The correction factor used may vary, depending on the microscope used. Since neutrophils tend to be pulled to the edges of a glass slide, lymphocytes tend to remain in the body of the smear, differential counts are done by examining cells in a pattern that evaluates both the edges and the center of the smear. After the count is complete, the percentage of each leukocyte type present is calculated and multiplied by the total leukocyte count to get the absolute number of each cell type present per microliter of blood. The absolute number of each leukocyte type is considered more important since relative values (percentages) can lead to wrong results when the total leukocyte count is abnormal (Harvey, 2005).

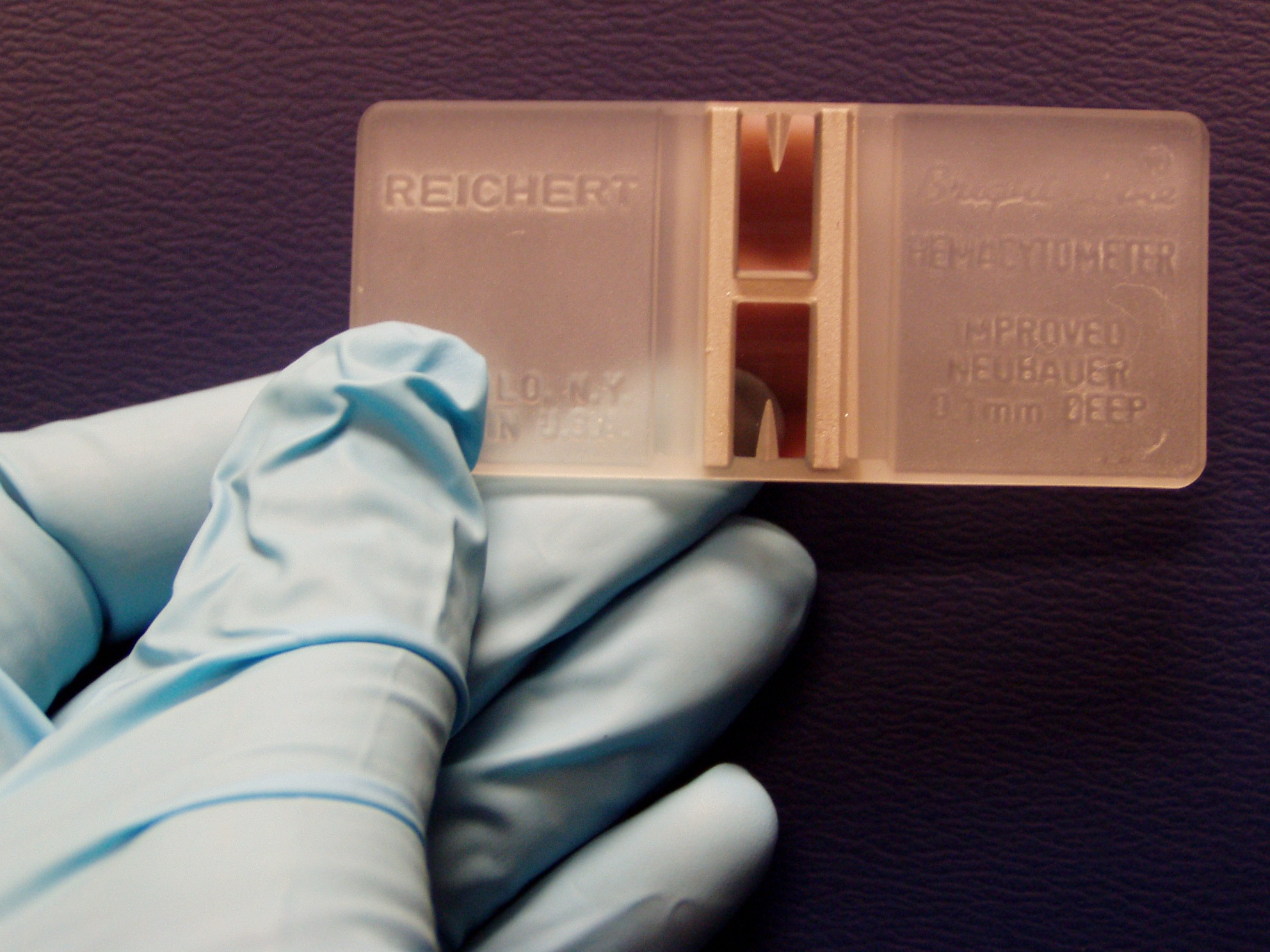

|

Manual: Leukocytes can be counted manually in specialised blood cell chambers.The sample is first diluted appropriately and then placed in a hemocytometer, most frequently the Neubauer chamber. Manual methods have a higher rate of error and are more time-consuming in general than automatic methods (Walker, 1990). We can use dyes to get a differential leukocyte count for example the May-Grünwald solution (eosin methylene dissolved in concentrated methanol and glycerine). The different leukocyte subtypes have differing appearances under the microscope after the dye has been applied which allows for them to be distinguished (Honda et al, 2016).

Automated: In general more accurate. However the presence of cryoglobulin or cryofibrinogen, aggregated platelets, nucleated erythrocytes or those that have been incompletely lysed will give an incorrectly increased count. In such cases manual counting is required (Weiss and Wardrop, 2010).

Impedance Counters: Standard method for leukocyte counts in body fluids other than blood. It uses changes in electrical resistance between an electrolyte solution and the cells in the sample being tested to count these cells. This method can result in falsely high counts in samples with thrombocyte agglutination, especially in animals such as cats who are prone to this phenomenon.

Flow Cytometry Counters: Flow Cytometry is a specialised hematology analyser and there are two methods:

Peroxidase staining method: Leukocytes are stained with peroxidase and can then be separated and counted based on the different rates of peroxidase absorbance in the different cell types. This method will also generate an automatic differential leukocyte count. It can also result in falsely high counts in samples with platelet clumping.

Basophil method: All cells apart from basophils are stripped of their cytoplasm and their nuclei are counted. This method separates the leukocytes by the light scatter as mononuclear cells (lymphocytes and monocytes), polymorphonuclear cells (eosinophils and neutrophils) and intact basophils.This is a more accurate way of leukocyte counting (Aroch et al, 2013).

Mammalian species have nucleated leukocytes and thus when counting we generally use methods that count nuclei so it is known as a “nucleated cell count”. However when dealing with birds, reptiles and fish we must use different methods of counting as their erythrocyte and thrombocytes are also nucleated (Tavares-Dias et al, 2008; Schnelle and Barger, 2012).

References

- Aroch I.; Targan N.; Gancz. A.Y. (2013). A Novel Modified Semi-direct Method for Total Leukocyte Count in Birds. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine 68(2).

- Barger, A. M. (2003). The complete blood cell count: a powerful diagnostic tool. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 33(6), 1207-1222. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(03)00100-1

- Bodnariu, A. (2008). Indicators of stress and stress assessment in dogs. Lucrari Stiintifice - Universitatea de Stiinte Agricole a Banatului Timisoara, Medicina Veterinara, 41, 20-26.

- Chan, Y.; Tsai, M.; Huang, D.; Zheng, Z.; Hung, K. (2010). Leukocyte Nucleus Segmentation and Nucleus Lobe Counting. BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1), 558. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-558

- Decaro, N.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, A.; Desario, C.; Mari, V.; Colaianni, M. L.; Buonavoglia, C. (2008). Experimental infection of dogs with a novel strain of canine coronavirus causing systemic disease and lymphopenia. Veterinary Microbiology, 128(3-4), 253-260. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.008

- Gyorffy, A.; Ronai, Z. (2011). Standard data, supplement for the physiology practical course. University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, 4.

- Harvey, J. W. (2005). Atlas of veterinary hematology: blood and bone marrow of domestic animals. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 45-47.

- Honda, T.; Uehara, T.; Matsumoto, G.; Arai, S.; Sugano, M. (2016). Neutrophil left shift and white blood cell count as markers of bacterial infection. Clinica Chimica Acta, 457, 46-53. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2016.03.017

- Jones, M.; Allison, R. W. (2007). Evaluation of the Ruminant Complete Blood Cell Count. Vet Clin Food Anim, 23, 377-402.

- Lilliehöök, I.; Gunnarsson, L.; Zakrisson, G.; Tvedten, H. (2000). Diseases associated with pronounced eosinophilia: a study of 105 dogs in Sweden. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 41(6), 248-253. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2000.tb03934.x

Maton, A. (1994). Human biology and health (2nd ed.) (J. Hopkin, C. W. Mc-Laughlin, S. Johnson, M. Q. Warner, D. La-Hart, & J. D. Wright, Eds.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Moore, D. M.; Zimmerman, K.; Smith, S. A. (2015). Hematological Assessment in Pet Rabbits. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 35(3), 617-627. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.05.010

- Peterson, M. E.; Nesbitt, G. H.; Schaer, M. (1981). Diagnosis and Management of Concurrent Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperadrenocorticism in Thirty Dogs. American Veterinary Medical Association,1(178), 1st ser., 66-69.

- Polizopoulou, Z. (2010). Haematological tests in sheep health management. Small Ruminant Research, 92(1-3), 88-91. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2010.04.015

- Ramoji, A.; Neugebauer, U.; Bocklitz, T.; Foerster, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Bauer, M.; Popp, J. (2012). Toward a Spectroscopic Hemogram: Raman Spectroscopic Differentiation of the Two Most Abundant Leukocytes from Peripheral Blood. Analytical Chemistry,84(12), 5335-5342. doi:10.1021/ac3007363

- Schnelle, A. N.; Barger, A. M. (2012). Neutropenia in Dogs and Cats: Causes and Consequences. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 42(1), 111-122. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.09.008

- Serrano, B.; Almeria, C.; García-Ispierto, I.; Yániz, J. L.; Abdelfattah-Hassan, A.; López-Gatius, F. (2011). Peripheral white blood cell counts throughout pregnancy in non-aborting Neospora caninum-seronegative and seropositive high-producing dairy cows in a Holstein Friesian herd. Res Vet Sci ,(90), 3rd ser., 457-462. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.019.

- Tavares-Dias, M.; Oliveira-Júnior, A. A.; Marcon, J. L. (2008). Methodological limitations of counting total leukocytes and thrombocytes in reptiles (Amazon turtle, Podocnemis expansa): an analysis and discussion. Acta Amazonica,38(2), 351-356.

Walker, H. K. (1990). Clinical methods: the history, physical and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.) (W. D. Hall & J. W. Hurst, Eds.). Boston: Butterworths, 724.

- WebMD (2009). "granulocyte". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 181.

- Weiss, D. J.; Wardrop, K. J. (Eds.). (2010). Schalm's veterinary hematology (6th ed.). Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Figures

[Fig. 1]Waterval, G. (2008) Petit Lymphocyte. [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons website: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6c/Small_lymphocyte-11.JPG

[Fig. 2]Segmented Neutrophils. (n.d.). [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons website: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/29/Segmented_neutrophils.jpg

[Fig. 3]Diaz, A. (2017). WBC Count Indication of Underlying Condition in Bovine Lymphocytic Specie. Own work of one of the authors of the page.

[Fig. 4]Jürgen, K. (2002). Toscana Schafe. [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons website: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ovis_aries#/media/File:Toscana_Schafe.jpg

[Fig. 5]Harrison, J. (2009). Oryctolagus cuniculus Tasmania. [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons website: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Oryctolagus_cuniculus#/media/File:Oryctolagus_cuniculus_Tasmania_2.jpg

[Fig. 6]Vinocur, J. (2006). A hemocytometer: each of the two semi-reflective rectangles is a chamber for counting cells. [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons website: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/18/Hemocytometer_with_gloved_hand.JPG