|

Size: 55226

Comment:

|

Size: 55230

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 42: | Line 42: |

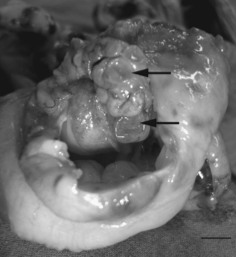

| ||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:center;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em; ;text-align:center"> {{attachment:ovarian.png||width=250}} <<BR>>'''Fig. 1'''<<BR>>''Left ovary of a 7-year-old female Bernese Mountain dog following ovariohysterectomy 229 days after administration of a 4.7- mg deslorelin implant, showing cysts varying from 5.0 to 12.0 mm in diameter (arrows) (bar1⁄41 cm)'' || | ||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:center;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em; ;text-align:center"> {{attachment:ovarian.png||width=250}} <<BR>>'''Fig. 1'''<<BR>>''Left ovary of a 7-year-old female Bernese Mountain dog following ovariohysterectomy 229 days after administration of a 4.7- mg deslorelin implant, showing cysts varying from 5.0 to 12.0 mm in diameter (arrows) (bar1⁄41 cm)'' || |

Different endocrinological aspects of mammalian reproduction

Contents

-

Different endocrinological aspects of mammalian reproduction

- Introduction: Presentation of Endocrinological reproduction

- Part I - Temporary and definitive inhibition of the secretion of sexual hormones in the bitch : contraception and sterilization

- Part II – The role of endocrinology in animal production : the dairy cow

- Part III - The reproduction system and the relation with the endocrinological part in the panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)

- References:

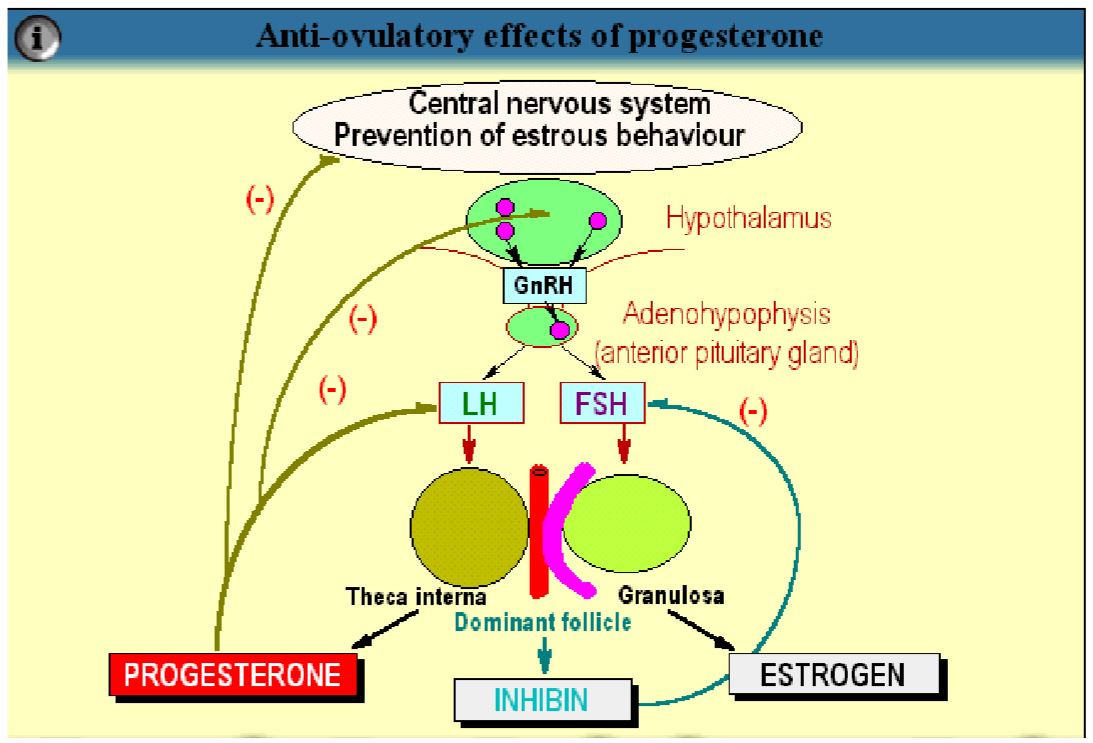

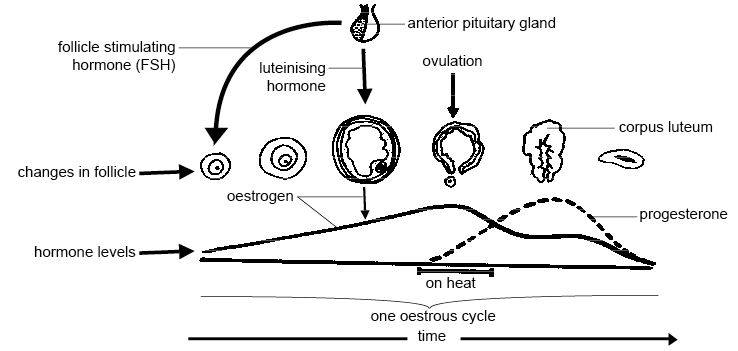

Introduction: Presentation of Endocrinological reproduction

Reproduction, by definition, is the biological process by which new individual organisms (« offspring ») are produced from their parents by combining the genetic material of 2 organisms (Wikipedia). Reproduction is one of the three primary needs of mammalian survival and has a role in supporting evolution. The neuroendocrine center, located in the Hypothalamus, acts as the major regulatory center of reproductive processes by mean of the action of hypothalamic GnRH cells that are going to stimulate all the hormones necessary to the control of reproduction. In the mammalian female, those hormones function by mean of a cycle which can be very different depending of species. Endocrinological regulation is a need in reproduction as it controls sexual maturity, normal sexual cycles, pregnancy, parturition and stability of the whole sexual mechanism.

How can Endocrinology affect or improve Reproduction in some mammalian species ?

Part I - Temporary and definitive inhibition of the secretion of sexual hormones in the bitch : contraception and sterilization

The reproductive cycle of bitches is different from that of women. Bitches undergo oestrus cycling from one to three times every 12 months. Mating and hence pregancy occur during oestrus. Infrequently, various factors such as ill health, can act to delay or suspend oestrus cycling. Unlike women, bitches do not experience a menaupose and usually continue to have seasons throughout life. Today they are numerous technics to avoid unwanted litters, but also behavioral and morphological changes characteristics to estrus.

1)Sterilization:

Sterilisation is the use of different medical techniques that intentionally supress the reproductive capacities of an animal/person and which is then unable to reproduce. It is a method of birth control. Sterilization methods include both surgical and non-surgical, and exist for both males and females. Sterilization procedures are intended to be permanent. The main reason, and the reason why all canine and feline welfare groups recommend sterilization for bitches, is to be able to have control over the birth of unwanted litters and of wild canid populations.

Endocrinology of sterilization : Ovarian and pituitary function in dogs after hysterectomy

Domestic dogs are monoestrous and predominantly aseasonal breeders, with several months of anoestrus between active reproductive phases (1). Compared to other domestic animal species, luteal function is practically similar in pregnant and nonpregnant females, except that pregnant animals attain baseline concentrations of progesterone earlier owing to the immediate prepartum decline of this hormone (2). The development of lactatio falsa (overt pseudopregnancy) in many nonpregnant bitches during the latter half of dioestrus might be related to this extended luteal lifespan (3). Endocrine control of gonadal, in principally luteal, function in dogs is unwell known. The fall of plasma progesterone concentrations after hypophysectomy during the early or midluteal phase (4) expose the necessity of pituitary support. Both luteinizing hormone (LH) and prolactin must be studied as luteotrophic. During the later luteal phase or late pregnancy, inhibition of prolactin by treatment with the dopamine agonist CB-154 significantly reduced progesterone concentrations (by >90%) or induced interruption of pregnancy (5). Injection of anti-LH-antiserum significantly reduced progesterone concentrations of plasma (by 76-93%) in pregnant bitches (6), but similar treatments during the early luteal phase induced only a tem¬ weak and less important decline of progesterone concentrations (7), demonstrating that the luteotrophic activity of LH and prolactin is related to the reproductive stage. The observation that prostaglandin F2a of endometrial origin induces luteal regression in most domestic animals (8) led to studies in dogs. A shortened luteal lifespan after hysterectomy was observed (9) (10) and a luteotrophic factor of uterine origin was postulated (10). Other observations chowed (11) a decline in progesterone concentrations after hysterectomy in normal pregnant dogs, but not in dogs with pyometra or other pathological uterine contents and concluded that there was a luteotrophic factor of fetoplacental origin. Neverless, observations demonstrate that they are no changes in luteal function after hysterectomy of pregnant and nonpregnant dogs (12), while a reduction of progesterone concentrations without a shortened luteal lifespan was reported (13). Reserchers (14) could not interrupt pregnancy after treatments with prostaglandin F2a, but observed only a temporary decrease in progesterone concentrations. Repeated treatments, however, induced abortions in some dogs at late stages of pregnancy; in the nonaborting animals, progesterone concentrations were reduced only temporarily (15). These data are opposing and only limited conclusions on whether and to what extent prostaglandin F2a of uterine origin acts as a luteolytic agent in dogs. In the present experiments, we attempted to define maintenance and resumption of gonadal function in intact and hysterectomized dogs by observing the animals over a long period and by monitoring progesterone and oestradiol concentrations. After determining prolactin in selected samples, it was hoped to gain related information on the availability of this gonadotrophic factor. Since pseudopregnancy is an inherent part of canine reproduction, possibly also resulting from interactions between luteal function and growth hormone (El Etreby, 1979), growth hormone was also determined in a series of samples.

Positive consequences : a commonly‐stated advantage of neutering bitches is a significant reduction in the risk of mammary tumours

An official justification for early neutering of bitches is that it protects against mammary neoplasia. However, many frequently cited references are over 40 years old (16). As part of a larger project to develop evidence-based guidelines for neutering bitches, the objectives of this study were to figure out the strength of evidence for the association between mammary tumours (of any histological type) and neutering, or age at neutering, and to estimate the degree, and confidence interval, of the effect of neutering, or age at neutering, on the frequency of mammary tumours (of any histological type) in bitches.

The effect of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours : Researchers on one hand (17) found a potent protective (approximately 10-fold) effect of neutering on the risk of malignant mammary tumours. Neverless, no confidence interval or P value was showed (while it was stated that the results were significant at the 5% level), and the results are only generalisable to animals from which samples are submitted for histopathological diagnosis. On an other hand, other researchers (18) reported “some protective effect” (no numerical data presented) of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours (benign and malignant combined) in beagles but concluded that the evidence was “inconsistent”. Finally, some (19) found no signifcant (P>0·1) confirmation of an association between neutering and the proportion of mammary tumour submissions that were neoplastic. However, this was only generalisable to dogs from which mammary samples were submitted for histology.

The effect of age of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours : Researchers (18) reported a convincing association between the risk of malignant mammary tumours and neutering before first oestrous [“relative risk” (RR) 0·005], second oestrous (RR 0·08), and after second oestrous but before 2·5 years of age (RR 0·06), compared with entire dogs. However, cases and controls were not straight comparable (as discussed above), there was a lack of clarity in how the relative risk was calculated, no confidence intervals were reported and results were again only directly generalisable to bitches from which samples are submitted for histopathological diagnosis.

There is some evidence to submit that neutering bitches before the age of 2·5 years is associated with a noticeable reduction in the risk of malignant mammary tumours, and that this risk may be reduced further by neutering before the first oestrous. However, our study, which involved screening over 10,000 articles in any language but reviewed only the English literature in detail, underlined that the strength of this evidence was weak because of the paucity of published studies that adequately address this issue.

Negative consequences : The ovarian remnant syndrome in the Bitch

The ovarian remnant syndrome is the existence of functional ovarian tissue in a previously ovariohysterectomized bitch. It is a complication of ovariohysterectomy, and it is not a pathologic condition.

Bitches with ovarian remnant syndrome show signs of proestrus and estrus defined by vulvar swelling, bloody vaginal discharge, behavioral changes like flagging and standing, and attraction of male dogs. (20), (21) Some bitches show clinical pseudocyesis, occasionally in the absence of a previously observed estrus. (20), (22) The bitch may allow copulation during estrus but do not become pregnant. The estrous cycles usually present the normal periodicity for that species. There may be a delay of months to years after the ovariohysterectomy was performed before the estrous cycles reappear.

Methods can be used in the diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome: Use of hormone assays to verify the diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome: A logical way to verify the presence of functional ovarian cortex is to measure serum estrogen concentration. Estradiol assays are available at many human and veterinary laboratories. An estradiol concentration greater than 20 pg/mL (73 pmol/L) is considered confirmation of follicular activity in the dog. A more decisive diagnosis can be obtained by using a hormone challenge or stimulation test: The administration of a pituitary gonadotropin or gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) during the follicular phase stimulates ovulation, formation of the corpora lutea, and a rise in serum progesterone concentration if there is functional ovarian cortex present.

||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:center;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em; ;text-align:center">

Fig. 1

Left ovary of a 7-year-old female Bernese Mountain dog following ovariohysterectomy 229 days after administration of a 4.7- mg deslorelin implant, showing cysts varying from 5.0 to 12.0 mm in diameter (arrows) (bar1⁄41 cm) ||

Fig. 1

Left ovary of a 7-year-old female Bernese Mountain dog following ovariohysterectomy 229 days after administration of a 4.7- mg deslorelin implant, showing cysts varying from 5.0 to 12.0 mm in diameter (arrows) (bar1⁄41 cm)

Figure 4: Left ovary of a 7-year-old female Bernese Mountain dog following ovariohysterectomy 229 days after administration of a 4.7- mg deslorelin implant, showing cysts varying from 5.0 to 12.0 mm in diameter (arrows) (bar1⁄41 cm).

Therapy : The treatment favorised as well as the method to establish the definitive diagnosis of the ovarian remnant syndrome is exploratory laparotomy with excision of the remnant tissue and histopathologic confirmation. Numerous surgeons favorise the surgery when the animal is in estrus, because the follicles on the ovarian remnant make it a better identification. Diestrus also is a good time to see the tissue, due to corpora lutea which are as easy to identify as follicles. Bleeding may be less during diestrus than estrus because of lower estrogen levels.

2)Contraception:

Endorcinology of contraception : Use of a GnRH analogue implant to produce reversible, long-term suppression of reproductive function of male and female domestic dogs

Repeated low-dose administration of a GnRH analogue is able of postponing oestrus in bitches and suppressing reproductive function in dogs. A new drug delivery formulation which could increase the practicality of this approach for the control of reproduction has been advanced.

Experience described on the bitches : The treatments expanded the length of the inter-oestrous interval at all doses and it was possible to postpone oestrus for periods of up to 27 months. Induced-oestrus was seen in all bitches treated during anoestrus, and during dioestrus when plasma progesterone was <5ng/ml, with the exception of two animals. Signs of pro-oestrus and oestrus were detected 4-8 days after implant placement in those bitches demonstrating induced oestrus. The treated pregnant bitches did not demonstrate an induced oestrus. At necropsy intact reproductive tracts were find and confirmed. Of the nine bitches mated at the first oestrus following recovery, six became pregnant. Of these, 2 were necropsied close to parturition and 4 gave birth to healthy litters. One litter was euthanased at birth, and 3 bitches raised healthy pups to weaning.

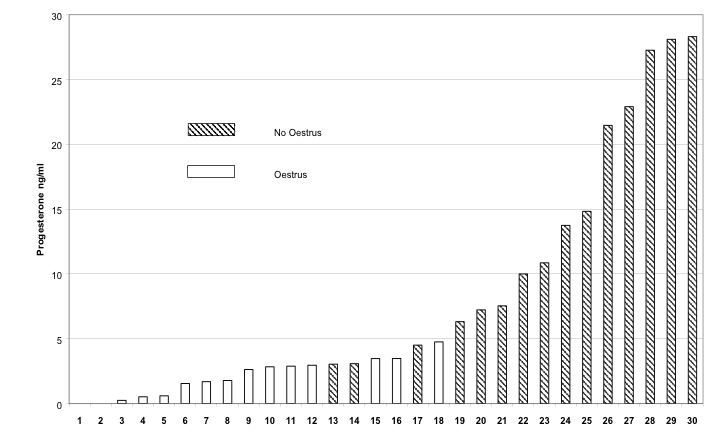

Figure 3 : demonstrates the effect of plasma progesterone concentration at the direct time of implantation on the incidence of induced oestrus in individual bitches succeding implantation with 3, 6 or 12 mg deslorelin. Each bar represents an individual animal.

Figure 3 : demonstrates the effect of plasma progesterone concentration at the direct time of implantation on the incidence of induced oestrus in individual bitches succeding implantation with 3, 6 or 12 mg deslorelin. Each bar represents an individual animal.

The study showed that single implant technology using deslorelin as a contraceptive agent perform a safe, long-term, reversible suppression of reproductive function in male and female dogs. The site of implantation did not demonstrate significant inflammation, acute or chronic.

Positive consequences of the contraception:

Contraceptive agent could be applied to the control of domestic and wild canid populations and also captive wildlife. But also for certain owners of domestic dogs to avoid morphological and behavioral changes which can in some cases be annoying. For example the loss of blood but also of a vaginal fluid, containing pheromones that can excite the male. The female also induce typical estral behavior for the purpose of attracting the male and eliciting copulation. Those changes are more a problem for people living in a city center.

Negative consequences : Follicular cysts and prolonged oestrus in a female dog after administration of a deslorelin implant

The case underline that the use of deslorelin implants in bitches may not be completely free of negative side effects and interactions with other hormones.

The concentrations of FSH and LH reported one week after administration of deslorelin were lower than those in the case presented here (23). Nevertheless, it is likely that down-regulation of GnRH receptors on gonadotrophic cells in the pituitary was complete.

Therefore the research beggined due to this suspicious down-regulation of GnRH receptors, thus hCG was adminitered instead of a short-acting GnRH analogue (24). The consequent increase in concentration of progesterone in serum indicated that the treatment with hCG provoked partial luteinisation of the granulosa cells of the cysts or receptive follicles, or it induced ovulation (25). The treatments, however, didn’t suppress production of oestrogen over a longer period. The ongoing output of deslorelin possibly interacted with the treatment or induced recurrence of the high concentrations of oestradiol. It is still unclear if the treatment would have been successful without the ongoing effect of deslorelin. The cysts examined histologically possibly grew within the period between the last ultrasound (26) and the ovariohysterectomy. Award the progesterone assay the corpus luteum identified was not hormonally active.

The emergence of pyometra may have been due to the treatment with hCG. The uterus was probably primed by high concentrations of oestrogen for several months. Raised concentrations of progesterone could have caused removal of local immune responses. The occurrence of pyometra in 2/15 bitches treated in dioestrus with deslorelin implants was observed (27). According to those authors the two cases may have been unrelated to the treatment as pyometra may develop spontaneously in any bitch.

Based on the last informations many controls should be done on the female dogs before performing the treatment (ei : ultrasonographic, gynaecological examination…ect). And the risk of side reactions seems to be higher in older female dogs, and dogs with apparent ovarian or uterine abnormalities.

Part II – The role of endocrinology in animal production : the dairy cow

Nowadays, the actual goals and roles of dairy farming is to produce more and more due to oppressing increase in population and demand. Heifers need to conceive earlier and get better production performances in average. To answer those actual questions, a perfect and well-managed knowledge of sexual endocrinological hormones is essential. This knowledge can be reinforced by the development of technologies such as Ultrasonography (monitoring follicular growth) and genomic technologies.

Rotatory milking parlor at a modern dairy farm in Germany

1) Effects of artificial endocrinology on early puberty and pregnancy in dairy heifers

Puberty is defined as « when ovulation is accompanied by visual signs of estrous and normal luteal function » and Pregnancy success as « correlated with percentage of heifers that reached puberty before or early in breeding season » (Perry, 2012) We also know that the optimal age for first conception in dairy cows is 2 years old ; and that can be apply by the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Control of Puberty

Several measurements can be made in order to control puberty; blood hormone concentrations are used to determine the pubertal process and the formation of the CL (Corpus Luteum). At puberty, the cow experiences a decrease in negative feedback of estradiol on GnRH followed by an increase in LH level. That will enhance the follicular growth and result in peripubertal period helped by estradiol secretion. Some recent studies have also showned a correlation between body conditions and normal estrous cycles. Indeed, a normal estrous cycle can be influenced by the age, the BW (Body Weight), the breed and size. An interesting study has proven that Leptin, the hormone for energy expenditure, had a role in regulation of HT/HP axis (Hypothalamus-Pituitary axis). Leptin levels increase at the age of puberty, therefore increasing the total BW. « Heifers can be developed to 50 to 55% of mature body weight before breeding season ». Heifers with lower body weight (53%) were seen being cycling before the start of the breeding season in contrast to heifers with more important body weight (58%). (Perry, 2012). Indeed, we assumed that the best body conditions for heifers to cycle and get pregnant was between 55 to 65% BW. Heifers with 65% BW conceived earlier in general during the breeding season.

Synchronisation of estrous cycle and fertility

An other fabulous discovery was to improve the synchrony of estrous and fertility by controlling both the follicular development and the luteal regression. 2 methods were studied : one based on the control of the luteal function and the follicular waves to improve the pregnancy success and the other related to the hormonal induction of new follicular waves (Perry, 2012). The fisrt method consists to synchronize the follicular waves by « prolonging the lifespan of a dominant follicle » (Perry, 2012). By using Progestin, we can follow the formation of « persistent follicles ». Those modified follicles have an extended lifespan and can increase the concentration of Estradiol (E2) and the LH pulse frequency. AI (Artificial Insemination) applied right after a treatment with Progestin will have consequences in decreasing fertility and alterating the uterine environment. Progesterone in that case will create a « turnover » and therefore make possible the regression and the initiation of new follicular waves (Perry, 2012). The second method focuses on initiating ovulation or atresia in the dominant follicle in a way to generate a new follicular wave. The experiments have shown that Progesterone and Estradiol was the best combination to initiate a new follicular wave after 4 to 5 days after injection. (Perry, 2012). However, GnRH injections were half effective compared the the latest and were also dependent of the stage of the estrous cycle. Further results demonstrated that Progesterone and GnRH injections were negatively related. Indeed, P4 and E2 are important in LH release and the so called “Presynchronisation” that allows a perfect time for the oestrous to optimally respond to GnRH injection and therefore initiating of a new follicular wave. This will have a positive impact on fixed-time AI. (Perry, 2012) That method can be reinforced by the so called “Ovsynch/TAI” (Ovulation-synchronized/Timed Artificial Insemination) protocol. The specificity of this protocol is that heifers can be inseminated at any stage of the oestrous cycle, meaning that no oestrous detection is realised before. A GnRH injection is given randomly during the oestrous cycle and that will initiate a new ovulation or luteinisation of large follicles necessary for the recruitment of new follicular waves. (F. Moreira, 2000)

Fertility

Different factors can play a role in enhancing fertility. One would be the AFC (Antral Follicle Count). This is strongly correlated with pregnancy success: a decrease in AFC will enhance a decrease in P4 and LH receptors. (Perry, 2012). AFC can also influence milk production and longevity because it promotes the optimal development of mammary gland tissue. An optimal AFC is situated between 23 and 24,5 months of age (D. C. Wathes, 2007). Some programs were tested to improve fertility, and that was the case of the so called “in utero” program, based on the relationship between maternal nutrition and some elementary factors such as growth, development and future reproductive performances in offspring. Studies demonstrated that cows restricted with food for the first 110 days of gestation had their calves with fewer AFC compared to the ones supplemented with rich nutrients that participated in increased conception rates. (Perry, 2012). Some other factors are influencing the fertility but will just be listed here: change in energy and protein intake, uterine environment, genetics (age at puberty, heritability…) and stress. Fertility has decreased over the past few years. We recorded a 60% fertility in 1970 in contrast with a 40% fertility in the early 20th century. (D. C. Wathes, 2007). A poor fertility can be the main factor influencing longevity. The actual solution is a better selection in younger ages. There are several investment stages in the production of offspring. The first would be the semen; its cost, quality, fertilisation rates, etc. A study showed that failures in fertilisation were the cause of 10% of the total losses (insemination at inappropriate oestrous time, embryo losses…) (D. C. Wathes, 2007). Based on the same studies we realised that only 40% of the total AI would result in birth.

2) Revue of endocrinological improvements on fertility and production in dairy cows : the role of AMH

First of all, we are going to focus on the Anti-Mullerian Hormone, a hormone similar to growth factor, part of the superfamily of the TGF (Transforming Growth Factor) and which is exclusively secreted by the granulosa cells of healthy follicles. We are going to demonstrate two studies that have proven that AMH is positively related to AFC, ovarian function/ovary size, fertility, birth weight and superovulatory response. AFC, as a reminder, is known as « the average for the maximum number of antral follicles superior to 3 mm in diameter during each of the 2 or 3 consecutive follicular waves during an estrous cycle » (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015).

1st experiment : AMH relationship with productive herd life

Initiation of experiment : Heifers with low AMH levels are more likely to have suboptimal fertility, poor reproductive performances leading to a shorter productive herd life and are most of the case removed from the herd.

Method of experiment : 281 heifers aged between 11 and 15 months old were tested by single measurement of AMH levels (blood prelevements on coccygeal vein). PGF2α injection was performed previous to the experiment in order to synchronize the estrous cycle. The heifers had to complete 2 lactations and a third one after calving. Different measures of performance and health parameters were also completed here. Both the level of AMH and the size of the ovarian reserve were measured. We applied AI the following day after « standing estrous » until successful pregnancy was diagnosed. To better interpret the results, we used quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) that correspond to the different levels of AMH : Q1 for lowest AMH concentrations and Q4 for the higest ones (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015). It is important to notice that, without knowing any result before the end of the experiment (i.e the end of the tree lactations), heifers with decreased or lower productive performances (including milk production, poor reproductive performances…) were intentionally culled.

Results : Heifers in the first quartile had shorter productive herd life, reduced survival rate after birth of the first calf, lowest milk production levels, lowest percentage of pregnancy and that quartile contained the highest percentage of culled heifers. However, the upper quartiles (Q2, Q3, Q4) showed longer productive herd life and with higher percentage of remaining cows. (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015).

Application(s) of experiment: Surprisingly, levels of milk production were not associated with AMH levels in dairy heifers. Ovarian reserve and function are said to be « moderately heritable in dairy cows » (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015) ; which can therefore be applied in the actual goals of reproductive herd performance : the AMH concentration and ovarian reserve - related gene selection, also called « AMH-related genetic markers » (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015).

Conclusion: By simple determination of AMH levels a diagnosis can be made to anticipate the future productive herd life of dairy cows and their tendency to produce better and in a longer period. “AMH can be a useful phenotypic marker to improve longevity of dairy cows” (F. Jimenez-Krassel, 2015). Furthermore, we can better understand the mechanisms contributing to the relation between AMH, fertility, level of milk production, longevity, etc.

2nd experiment: AMH relationship to super ovulatory response

Initiation of experiment: As defined earlier, AMH gives us information about the ovarian follicular reserve and its main role is to “modulate early follicular growths and inhibit excessive number of follicles from entering growing follicle pool” (A. H. Souza, 2015). This experiment has demonstrated the positive relation between AMH plasma levels and the number of large follicles and CL after both super stimulation and superovulation.

Method of experiment: blood samples from approximately 70 cows were taken at 3 different stages of synchronized oestrous cycles (PGF2α injections). Transrectal ultrasonography was used for embryo collection.

Results: The same analysis with quartiles was applied. To investigate the results, “animals with 3 or more CL at the time of embryo collection were considered to have responded to the superovulatory treatment” (A. H. Souza, 2015). Q1 seemed to have the lowest superovulatory response compared to the fourth one. Upper quartiles had the following advantages: a greater number of fertilized structures and better transferable and freezable embryos. AMH was then strongly correlated with superovulation response but not to the percentage of fertilized embryos. Additionally, AFC was said to be the primary source of circulating AMH. The results above can demonstrate the “hypothesis that AMH concentrations are predictive of superovulatory response”. Indeed, this method can serve for precise synchronisation of follicular wave before superovulation and therefore evaluating the ovarian reserve. Here, the practical point of view is essential to facilitate new implementations of that technology and to reduce the costs in embryo selection. Another important factor that can be emphasized in that case is the correlation with the body weight (BW). BW can positively alter the circulating AMH concentrations. In opposition to that, “the decrease in AMH may reflect reduced antral follicle numbers in cows with greater BW loss” (A. H. Souza, 2015).

Conclusion: The circulating AMH levels are positively correlated with superovulatory response and “embryo production potential of individual cows” (A. H. Souza, 2015). This study shows again a large improvement in embryo-transfer programs concerning dairy cows. Finally, the importance of genetics (AMH-related genetic markers) and those essential parameters studied in both experiments can bring us to a new vision of artificial selection in dairy cattle, strongly influenced by technological advances.

3) Effects of environmental heat stress on reproductive performances in dairy cows

By definition, stress is the “condition where there is undue demand for physical and mental energy due to excessive and adversive environmental factors and cause deformations those are identifiable through physiological desequilibrium” (Abrar Ahmed, 2015). Nowadays, Heat Stress (HS) is considered as a major economical and environmental issue and might lead to economical losses mostly in tropical and some temperate regions, consequences of the climate change that sees its temperatures increasing by 0,2°C in average per decade (Ramendra Das, 2016). The comfort of the dairy cow can be evaluated using the so called term “comfort zone” where energy expenditure of the cow is at its minimum and may be influenced by its age, breed, diet and feed intake. We say that the animal is in HS when it is outside of its comfort zone. The normal body temperature of the cow is between 38,4 and 39,1, its thermoneutral zone ranges from 16 to 25°C. Above an outside temperature of 20-25°C we can say that the cow experiences heat gain which will later result in HS (Ramendra Das, 2016). According to recent studies, we distinguish two types critical temperatures. First the Lower Critical Temperature (LCT) where the “Animal needs to increase its metabolic heat production to maintain its normal body temperature” and second the Upper Critical Temperature (UCT) that makes the animal to elevate its heat production by a rising in body temperature or evaporative heat loss. (Abrar Ahmed, 2015). Those critical temperatures are the consequence of HS and can be manifested by decreasing milk production and reproductive performances.

HS is the cause of several reproductive functions

This table summarises the different effects that HS can cause on reproduction and show how much reproductive functions can be altered by its effect. HS in a general way suppresses endocrinology and immunity of the animal.

Reproductive function |

Effects of climatic stress on associated physiological functions |

Pubertal development and Estrous Induction |

↘ length + intensity of estrous; ↘ Follicle selection; ↗ Follicular wave length; ↘ Oocyte quality; ↘ LH + E2 synthesis --> blocking of E2-induced sex behaviors |

Hypothalamus/Pituitary Ovarian Axis |

General desynchronisation GnRH secretion ↘ leading to E2 secretion ↘ --> HS effect is then increased PRL is heat sensitive, ↗ levels in summer period --> Anti-GnRH action; ↗ ACTH and Cortisol production |

Fertility / Conception |

↘ Fertility rates (both summer and fall seasons); ↗ PRL --> Acyclia! and infertility |

Embryonic development |

↗ embryo losses (most of the case the consequence of maternal HS) Biggest losses around first 2 weeks of pregnancy 40 to 60 days are necessary after HS for fertility to come back to normal state (undamaged ova ovulated); ↗ Fetal abortions --> embryo death (oxidative cell damage) |

Oocyte performances |

↘ Follicular development --> ↘ steroid hormone production + follicular growth --> Incomplete dominance of selected follicle; ↘ Decrease competence of oocytes |

Table 1 – Effects of Heat Stress on sexual reproductive functions

Milk production is decreased

Indeed, dairy cows need to have a very efficient and high level metabolism that help them to produce larger quantity of milk every day. When milk production becomes intensive, for example at the lactation peak (4 weeks), heat metabolism is present and heat stress is induced, having strong negative impacts on milk synthesis. Therefore dairy cows are more sensitive and fragile to HS as milk production is getting bigger and bigger. According to some deeper studies, the mechanism is the following: HS influences the activation of “stress response systems in lactating cows” (Ramendra Das, 2016) that will have a negative effect on feed intake. By decreased of food intake, milk production will be lower, such as the DMI (Dry Matter Intake) that can be decreased by 0,85 kg every 1°C rise in temperature, inducing up to 36% decrease in milk production. (Ramendra Das, 2016) To face that issue, several methods were applied but Selection was the most accurate one. By selecting for milk yield, we can attenuate the thermoregulatory range of dairy cows, then “magnifying the depression in fertility” that can be a cause of HS (Abrar Ahmed, 2015).

Solutions and answers to Heat Stress

One of the most known solutions to elevate summer fertility management is the introduction of Artificial Insemination (AI). This program, described earlier, does not need any estrous detection but does not act against the effects of climatic temperatures. Finally the most accurate and simple method to fight HS is the cooling method that can both increase reproductive performances and milk production.

Part III - The reproduction system and the relation with the endocrinological part in the panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)

The panda is an animal who lives in the tropical and damp area, around the mountain of China and the Tibet. The wild panda is a very discreet animal. Nowadays, they count only 1750 pandas. The deforestation and the exploitation of the bambou are taking a real part in their disparition but also fur-poaching. That’s why the reproduction of the panda became a real goal for the association of the animal protection like World Wild Foundation for sustaining the population. But considered like a « rare species » the reproduction of the panda is not that easy. In this research, we will clarify panda reproduction and understand how it works, in relation also with the endocrinological part.

1)The general part of the reproduction of the female panda, general characteristic

Researchers have found that lots of males compete for each female during mating and breeding season. The dominant male can mate with a female lots of times for giving chance to a new pregnancy of younger pandas. It helps for each fertile female to become pregnant. Wild giant pandas usually give birth every two years for about 15 years. Giant pandas reach sexual maturity at 5.5 to 6.5 years. The mating season is in spring between March and May and gestation takes from 95 to 160 days. The female giant panda has a single estrous cycle once a year in spring for 2 to 7 of those days. And only fertile for 24 to 36 hours. This short period indicates such a tough challenge for sustaining the population.

Estrous cycle and hormonal part; ovulation and pregnancy :

In this experiment, data is collected by females between 5 to 7 years during the three mating seasons of 1997–1999. Showing a high degree of regularity in both estrogen and the behaviors when using artificial insemination gives the confirmation of the time of the ovulation of the panda occurring right after a peak in estrogen values present in urine (lindburg 2001). The female panda produces a single estrogen peak during the spring mating seasons (three successive years) on April 24, April 9, and April 9. The normal value is <50 ng/mg Cr of estrogen begin around day –11 and the peak is just >600 ng/mg Cr, following by a decrease precipitously to the normal value on the next 2 days. (lindburg 2001) The pregnancy via artificial insemination on the days 1, 2, 3 in the three seasons accept the hypothesis that the period after day 0 is the period when ovulation occurs. But it is not so precise for identify the temporal connexion between the release of the ovum and descending ostrogen values. (lindburg et al 2001)

In another expriment, measures of urinary estrogen and progesterone during oestrus and pregnancy in panda were taken. Urinary estrogen were more present and excreted during oestrus and was identified as estrone glucuronide which can be calculated directly or with estrone after hydrolysis and extraction. (Hodges et al 2009) Ovulation can be shown by a rapid increase of estrone, which will be held on the onset of oestrus between two to four days. More precise timing for the ovulation, necessary timing mating or artificial insemination, can be demonstrated by monitoring the subsequent decrease in estrone excretion. A direct assay for estrone-3-glucuronide which can be done within two to three hours, gives the most practical and fast method to seek ovulation in the Giant panda (Hodges et al 2009).

Baby giant pandas are born in an extremely critical state, babies are blind, toothless, and only sparsely covered with white fur. They are less formed and have a litter size ranges from one to two, captive females are reported to rear only a single young. Infant giant pandas walk and move poorly until four months of age and can be weaned in captivity by 6 months of age when they grow up and take 13kg around. A giant panda of one year old and who has only an average of 36 kg or about a third of an adult weight has a good health. (Kleiman 2010).

2)Hormonal part of the reproductive system in the female panda, the way to understand and improve the reproduction

The estrogen discharges were measured in 10 females via different immunological way: -six of them by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) of the estrone glucuronide analysis -four of them by the method of the radioimmunoassay (RIA) of the estrone sulfate analysis

These results will be compared with the two different immunological ways. The measurement of data will be based on the urinary estrogen excretion profiles in four pandas and who the reproduction is well successful because it takes place after the days of insemination. The research of urinary progestins and also to estrogens, can be put in relation with the monitoring of reproduction in the giant panda. It can help in the exposure of the development of a corpus luteum who will produce the ovulation, and as a monitor for gestational changes. In this research we will seen the progestin dynamics surrounding ovulation in six pandas, make a conclusion of hormone excretion in the six giant pandas that we studied to date. (Czekala et al 2003).

Also we will show how the endocrine data can be taken as a specific place to enhance animal management and maximize reproductive success. Urine was taken up every day as conditions allowed, since it was not possible to collect from all animals each day. A needle was used to take the urine from the cage floor, and once collected it was placed in labeled cryo tubes for storage. Urine was stored in a cold place until analysis. All hormone concentrations are indexed by creatinine (Cr) in order to adjust for variability in the urine dilution from sample to sample. Results are expressed as mass/mg Cr. (Czekala et al 2003)

Immunoessay techniques: Estrogens ( RIA/ ELISA/ EIA) HPLC (urine sample with peak of estrogen concentration ) Progestins ( The measurement of the pregnanediol-3-glucuronic by EIA, and peak of estrogen concentration need for find the good timing go the ovulation).

The time of ovulation and the estrous was detected with the RIA and ELISA immunological assay thats to the urinary estrogen. The results of estrogen secretion for the two methods were practically the same. Between the day 0 and the day 10, the urinary estrogen began to increase, meaning the ovarian follicle become mature, the process starts.

For the group of the six panda the EIA is used for monitor the estrous, the results are:

- a.-6 ng/mg CR/ day -14 to -12

- b.-6-15 ng/mg CR/ day -11 to -7

- -And after a huge peak of CR concentration at day 0

For the group of the female analysis with RIA: Urinary estrogen:

- a.-o40ng/mg Cr/ day -25 to -14

- b.-40-50 ng/mg Cr/ day -13 to -10

Continued with a elevated peak of concentration at the day -9 until day 0. McGeehan (personal communication) and others [Bonney et al., 1982; Chaudhuri et al., 1988; Hodges et al., 1984; Monfort et al., 1989; Murata et al., 1986], thanks to them they discovered that the peak of the receptivity of the sexual function of the female is in relation with the decrease of estrogen concentration. Also, thanks to this research the pregnancy was found at the day 135 after the first insemination. (Czelaka et al 2003).

The results of a comparison of the time of peak estrogen excretion with the days of insemination, by natural mating or AI, in females that gave that the results of estrogen levels in all groups of females except on female was completed after mating and AI. The works of the urinary estrogens, or also by urinary estrone glucuronide or estrone sulfate, is a really good aid of monitoring impending ovulation, and can be served as a timing tool for mating introductions and AI. The calculations informed that there is an approximately 10-day arrangement of gradually increasing estrogen excretion and follow the pre-ovulatory estrogen peak and which is proceed by a rapid decline to the base of the data. (Czekala et al 2003).

The study used a ‘‘direct’’ method through the use of HPLC. When looking of the percentages of estrone metabolite components present in the urine, both way for find the estrone conjugates indicate arrangement of estrogens increasing at estrus and dropping juste after the the time of ovulation.The urinary hormones of the panda shown that the increase of estrogen concentrations have a relationship with the increase in reproduction behaviors, and that peak receptivity usually occurs after the fall of estrogens to base line.

The rising of progesterone metabolite excretion leads to an ovulation in the giant panda, however, the present works and research are using an antiserum with a broader spectrum of cross reactivity than that previously studies. Here, the progestin concentrations of the day 7 post-estrogen peak were four times the base of the concentration data. Progestin analysis, can be used like a way to show that ovulation has occurred following the dropping of estrogens. (Czekala et al 2003).

3)Overview of the reproduction: the male giant panda

The reproduction of giant pandas is a real goal and particularly males. Because, with experiences we demonstrate that males have low libido and/or aggressive behaviors toward females. The increase of the genetic heterozygosity in the ex situ population of 120 giant pandas in China permitted the potential reproduction in the future, but, it is essential that all the panda can be in good condition for breed. Artificial insemination of fresh semen takes a real place in the role of the reproduction of giant pandas in captivity, including aid to regulate the problem of sexual incompatibility.

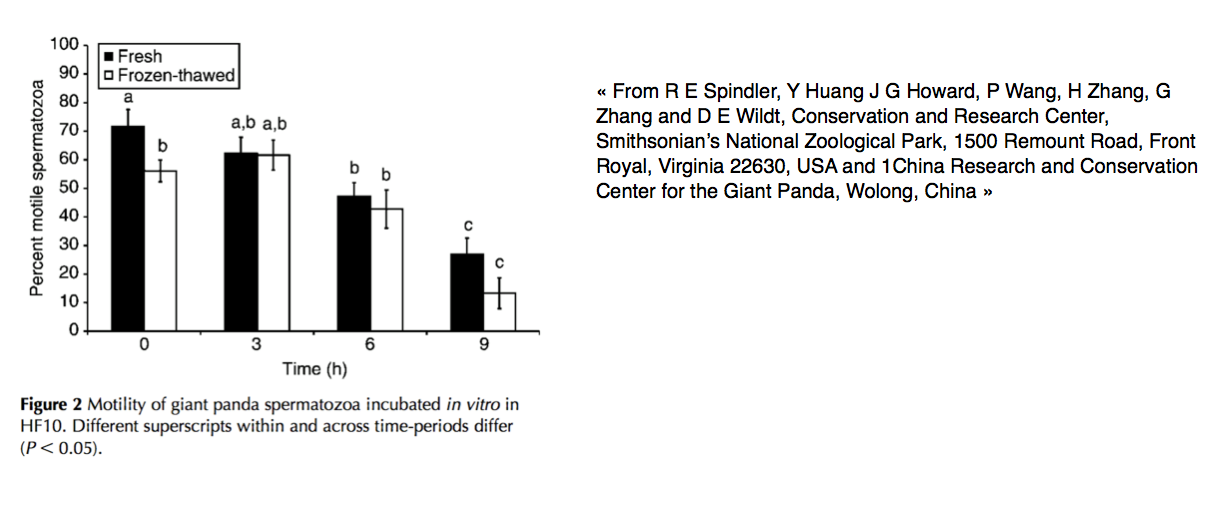

Almost all the AI are successfully complete and have occurred with fresh spermatozoa method, the genetic engineering of giant pandas in captivity is made out as the one of the first priorities for ex situ conservation action in China. The ability to every time making new offspring by the methods like cryopreserved sperm would permit to extend the sperm viability from days to years and even generations.

This significantly increases the predicted survival of panda. So, the effective sperm cryopreservation in theory can allow securing robust genetic material of wild giant pandas which are captured for brief periods. Sperm from these pandas can be taken in consideration of ‘insurance’ for the gene pool, with aliquots used periodically to infuse heterozygosity into the ex situ population. This would eliminate the need to over extract more giant pandas from native habitats to support zoos. Functional viability of a spermatozoon generally depends on sperm progressive motility, acrosome integrity and the ability to undergo capacitation, the acrosome reaction and decondensation. Capacitation is the terminal stage of sperm maturation and is needed for the acrosome reaction and subsequent zona pellucida (ZP) penetration and oocyte fertilisation.(Spindler et al 2004)

The work will be held of series of investigations to determine the influence of seminal processing and cryopreservation/thawing on giant panda sperm function. Here, we will study on the phenomenon of sperm capacitation in vitro. Spermatozoa of some species can make capacitation spontaneously in vitro, whereas others require accelerators such as 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine or dibutyryl cyclic AMP (dbcAMP). At the end, the goal is to find the dynamics of giant panda sperm capacitation in the presence and absence of IBMX and dbcAMP. Cryopreservation is also seen to block the sperm function via damaged acrosomal membranes. And in a second way to determine if the freeze–thawing induced membrane damage is reducing the ability of giant panda sperm to get acrosome reaction.

Results:

The spermatozoa of the Giant panda were capable of capacitating in vitro over a 6-h interval of incubation with or without the use of the accelerators IBMX and dbcAMP. Plus, a little loss of cellular motility post-thawing appear, the methods described here followed the freeze–thawing of giant panda sperm without compromising acrosomal integrity. The ursid and felid zonae emulsions help the acrosome reaction in giant panda spermatozoa, supporting data who shown that the triggers to this phenomenon are not species specific. But, the methods utilised here for freeze–thawing these cells did not compromise the ability of giant panda sperm to undergo capacitation. To permit a successful fertilisation, this research indicated the importance of sperm motility and acrosome integrity, the discovery of a high level of motile, and acrosome-intact sperm after cryopreservation. Results were promising, but still not enough for normal fertilisation. This incidence of damaged acrosomes found in thawed, CHF10-incubated and also control sperm over time could be explained by contact with other sperm or the plastic incubation tube around thawing process. Spermatozoa can be damaged or premature ‘capacitation-like’ changes can happen during freeze– thawing, or exposure to medium which have accelerators. Alternatively, these sperm labelled damaged can be practically capacitated sperm. (Spindler et al 2004).

References:

1. Stabenfeldt & Shille, 1977; Siegel, 1982

2. Concannon et ai, 1978

3. (Shille & Stabenfeldt, 1980; Concannon, 1987; Gerres et ai, 1988)

4. (Okkens et ai, 1986)

5. (Conley & Evans, 1984; Concannon et ai, 1987)

6. Concannon et ai, 1987

7. Conley & Evans, 1984; Concannon et al., 1987

8. (Anderson et ai, 1969) 9. Baker et al. (1980)

10. Both Hadley (1975)

11. Chaffaux & Thibier (1978)

12. Olson et al. (1984)

13. Okkens et al. (1985)

14. Jöchle et al. (1973)

15. (Concannon & Hansel, 1977)

16. Frye 1967, Dorn and others 1968, Schneider and others 1969

17. Schneider and others (1969)

18. Bruenger and others (1994)

19. Richards and others (2001)

20. Manfra-Marretta S, Matthiesen DT, Nichols CE: Pyometra and its complications. Prob Vet Med 1:50, 1989

21. Pearson H: The complications of ovariohysterectomy in the bitch. J Small Anim Pract 14:257, 1973

22. Shemwell RE, Weed JC: Ovarian remnant syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 36:299, 1970

23. Reichler et al. 2006

24. Shille et al. 1984

25. de Gier et al. 2006

26. Day 188 after implantation

27. Volkmann et al. (2006)

28. J. Reprod. Fertil. (November 1, 1992) 96, 837-845. Ovarian and pituitary function in dogs after hysterectomy.

29. W. Beauvais, J. M. Cardwell and D. C. Brodbelt. Veterinary Epidemiology and Public Health Group, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hatfield, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA. The effect of neutering on the risk of mammary tumours in dogs – a systematic review.

30. Melissa S. Wallace, DVM. Canine Reproduction. 0195-5616/91. The ovarian remnant syndrome in the Bitch

31. Aris Junaidi, Graeme B Martin. Article in Journal of reproduction and fertility. Supplement · January 2001. Use of a GnRH analogue implant to produce reversible, long-term suppression of reproductive function of male and female domestic dogs

32. SP Arlt , S Spankowsky & W Heuwieser (2011): Follicular cysts and prolonged oestrus in a female dog after administration of a deslorelin implant, New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 59:2, 87-91

33. A. H. Souza, P. D. Carvalho, A. E. Rozner, L. M. Vieira, K. S. Hackbart, R. W. Bender – Relationship between circulating anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and superovulatory response of high producing dairy cow, (2015)

34. Abrar Ahmed, R. P. Tiwari – Effects of environmental heat stress on reproductive performances in dairy cows, (2015)

35. D. C. Wathes, J. S. Brickell – Factors influencing heifer survival and fertility on commercial dairy farms, (2007)

36. F. Jimenez-Krassel, D. M. Scheetz – Concentration of anti-Mullerian hormone in dairy heifers is positivey associated with productive herd life, (2015)

37. F. Moreira, R. L. de la Sota – Effect of day of the estrous cycle at the initiation of a timed artificial insemination protocol on reproductive responses in dairy heifers, (2000)

38. Perry, G. A. – PHYSIOLOGY AND ENDOCRINOLOGY SYMPOSIUM : Harnessing asic knowlegde of factors controlling puberty to improve synchronization of estrus and fertility in heifers, (2012)

39. Ramendra Das, L. Sailo, N. Verma, P. Bharti – Impact of heat stress on health and performance of dairy animals : A review, (2016)

40. (Short and Bellows, 1971)

41. (Ferrell, 1982; Freetly and Cundiff, 1998)

42. (Patterson and Bullock, 1995; Wood-Follis et al., 2004; Leitman et al., 2008)

43. D.G. Lindburg, N.M. Czekala, and R.R. Swaisgood (2001) Hormonal and Behavioral Relationships During Estrus in the Giant Panda: Giant Panda reproductive cycles. Zoo Biology 20: 537–543

44. J. K. HODGESD, . J. BEVANM, . CELMA*J,. P. HEARND, . M. JONES, D. G. KLEIMAN*J*., A. KNIGHT and H. D. M. MOORE (2009) Aspects of the reproductive endocrinology of the female Giant panda (Ailuropodu melunoleacu) in captivity with special reference to the detection of ovulation and pregnancy J. Zool., Lond. 203: 253-267

45. By DEVRGA. KLEIMAN (2010) - Ethology and Reproduction of Captive Giant Pandas- Tierpsychol., 62: 1-46.

46. Czekala, Karen Steinman, Laura McGeehan, Li Xuebing,Fernando Gual-Sil (2003) Endocrine Monitoring and its Application to the Management of the Giant Pand - Zoo Biology 22 :389–400.

47. R E Spindler, Y Huang, J G Howard, P Wang, H Zhang, G Zhang and D E Wildt (2004) Acrosomal integrity and capacitation are not influenced by sperm cryopreservation in the giant panda, Reproduction 127: 547–556