Manipulation of the estrous cycle in the bitch

By Sara Kjær, Hanna Knutsen and Ingeborg Marie Vatne

Content

Contents

Introduction

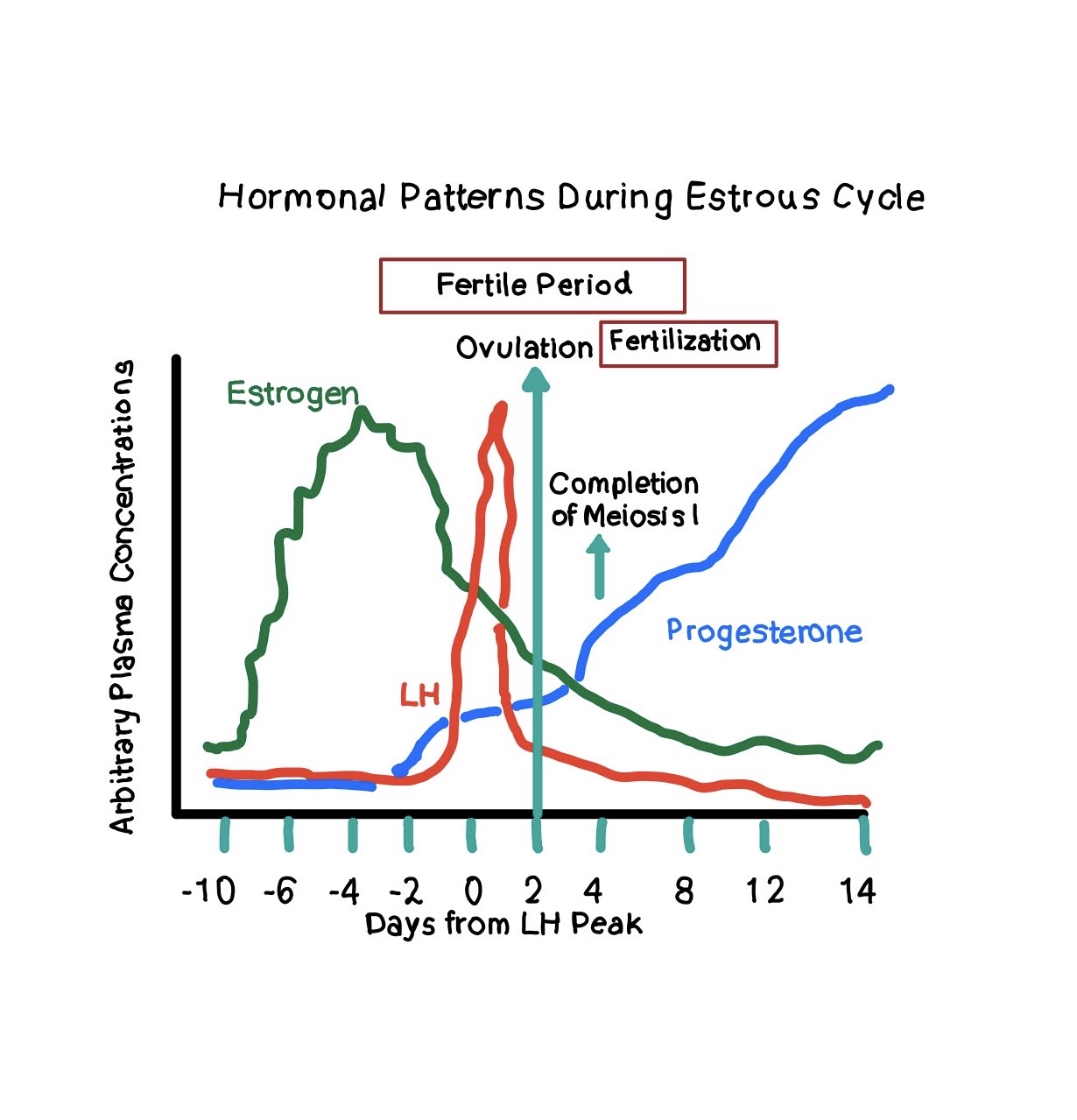

The estrous cycle is cyclic processes of the female reproductive system, and the period between two consecutive ovulations. There are four distinct phases of the estrous cycle: proestrus, estrus, metestrus and diestrus (depicted in Figure 1). The lack of estrus cycle is called anestrus. Some species show seasonality, and the estrus cycle varies according to the different animals. We will in this essay mainly focus on the dog’s estrous cycle. The length of the estrus cycle in the bitches is approximately 2 months, which in comparison to the other species is relatively long.

With few exemptions the average bitch ovulates once or twice per year. Unique to the dog we find an inter-estrus interval (IEI), the time from onset of one proestrus cycle to the next, that includes proestrus, estrus, diestrus and anestrus. This interval usually ranges within 16-56 weeks, yet individual variations may be seen. During manipulation of the estrous cycle it is therefore the shortening and lengthening of IEI that is altered.

Nowadays manipulation of the estrous cycle has become a common request of dog owners for different reasons. On one side, owners may be interested in temporally preventing estrus until the bitch has finished her career, or to manage the kennel in the presence of a stud dog and to avoid undesirable breeding. Additionally, owners with no interest for breeding, may, for ethical reasons, prefer to avoid elective surgery such as ovariectomy, to control reproduction. On the other side, the owners may want to induce estrus to better control the time of birth, to use a male with limited availability during a specific time, or to reduce the duration of the inter-estrous interval in bitches with a long estrous cycle.

Figure 1 Different stages of the monoestrous cycle |

The physiology of the estrus cycle and its relevant hormones

Hormones are extremely important regarding the regulation of the estrus cycle. In estrus, changes in behavioral and hormonal levels occur simultaneously at multiple levels; ovary, uterine duct, uterus cervix, vagina. The highest center of regulation of reproductive hormones processes is located in the hypothalamus. The regulation is strongly linked to other hypothalamic regulatory mechanisms, for example energy balance and food-intake. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), Progesterone (P4), estrogens, Prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2a) and prolactin (PRL) are among some of the most important hormones related to the female reproduction. They have different roles varying from follicle maturation and inducing ovulation, to inhibiting lactation during pregnancy. Knowing their importance in relationship to the estrus cycle, we can understand that regulation of these hormones is a possible way of manipulating the estrus cycle in the bitch.

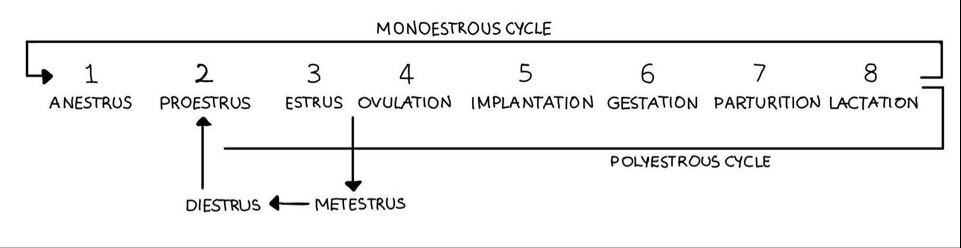

Hormonal changes during the estrous cycle

Hormonal changes during the estrus cycle is crucial in order to understand the different phases of the cycle (depicted in figure 2). During ovulation, there is a high level of estrogen, a high level of GnRH which induces a LH-peak, resulting in ovulation. The LH-peak, indicated by up to 200-times higher concentration than baseline LH secretion, induces the ovulation and luteinization processes. The luteal phase in dogs shows a significant difference in P4 levels compared to other animals. The Progesterone levels starts to elevate before the ovulation (approximately 24 hours), this gives the opportunity to determine the exact timing of ovulation in the bitch, by checking the plasma P4 concentration. Luteolysis is the end of the luteal phase, and if the animal is not pregnant, PGF2a is produced by the uterus, which causes the lysis of corpus luteum. At the follicular phase we can see an elevating level of FSH hormone, which induces the next ovarian cycle.

Figure 2 Hormonal levels during estrous cycle |

How to manipulate?

For several decades' researchers have been studying different options to alter and stifle fertility. This is mainly to handle over-population and wildlife but when extracting its benefits, it can be applied in the case of domesticated animals as well. For wildlife populations immunocontraception has been commonly used, but with the downside of not providing long-term infertility. Immunocontraception involves stimulating immune responses against gametes or reproductive hormones thus preventing conception (Cooper and Larsen, 2006). There are several fundamental issues with this approach ranging from the difficulty obtaining self-antigen responses to the likely evolution of genetically based non-response to immuno-contraceptive agents. This form of contraception and thereby alteration of the estrous cycle has therefore been attempted as a non-surgical alternative in the bitch (Maenhoudt and Santos, 2018).

As the physiology of the canine reproductive system is unique it makes it difficult to apply measures that would otherwise have effect in other domestic animals (Kutzler, 2018). When exploring different options, it will be worth mentioning the use of Progestins and Androgens as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone and dopamine agonists.

Already in the 1960s were progesterone introduced as a method for preventing estrus in the dog. Its opposite, inducing estrus, came first twenty years later. Implementing dopamine agonist provided the induction needed to alter the estrus cycle. The use of GnRH-agonists for the same purpose came in to work later and have prevailed.

Progestin

The use of synthetic progesterone (progestin) is the oldest, most spread form of estrus prevention several different formulations have been made available. These formulations alter in their affinity to the intracellular progesterone receptor (PR) as well as in their administration routes. By daily administration tablets can be given orally which can postpone estrus for a short time. Injections on the other hand can provide a longer acting effect and be applied in intervals of 3-5 months.

Progesterone, a steroid hormone, is naturally secreted by the corpus luteum (Dyce, 2010) and function to regulate the lining of the uterine endometrium. The mechanism of its synthetic counterpart, progestin, is not fully understood in the terms of its contraceptive activity. It is presumed that it affects the luteal phase by mimicking the effect of progesterone as well as its affinity to PR. Studies have only shown scarce (Günzel-Apel, 2009) or no influence (Colon et al, 1993) on the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis which is responsible for the hormonal regulation. It has however, been well documented that the use of synthetic progesterone does, in most cases, inhibit the various phases of the ovaries. It is presumed that the synthetic form modulates the FSH and LH secretion and therefore suppress the follicle development.

Androgens

The use of androgens has also shown a potential in preventing estrus. Testosterone and its derivates have an anabolic characteristic and therefore a decreased availability in most countries. Treatment with androgens provide an effect through the negative feedback on the hypothalamus. By a specific concentration of the gonadal hormone the negative feedback will downregulate the release of other hormones as well. It will mainly affect the GnRH and thereby also the downregulation of FSH and LH (Linde-Forsberg, 2001).

Using compounds of testosterone will in addition provide certain advantages for the bitch’s genital tract. The effects provided by synthetic progesterone, such as cystic endometrial hyperplasia, can therefore be avoided. However, this type of treatment can induce other side effects such as masculinization. This can be seen in the form of increased muscle mass and behavioral alterations such as an increase in aggression and vocal change (Maenhoudt, 2018). The applications of all the above-mentioned ways of treatment should be given during anestrus or at the first observable sign of proestrus. This will provide a stronger desired effect and decrease the risk of pregnancy as well as suppressing other hormonal changes. These changes may vary from vaginal bleeding and attraction to males.

Bromocryptine

The dopamine agonist bromocryptine was found to be suitable for provoking fertile estrus during the anestrous phase in bitches without functional cycles and/or ovarian activity (Zöldág et al, 2000). Bromocryptine is an orally or parenterally administered semisynthetic ergot alkaloid. It is assumed that Bromocryptine acts as a dopamine agonist and prolactin antagonist, thus reducing the duration of the luteal phase, and consequently the time between two estrus cycles. The assumption is based on that in bitches, in addition to LH, prolactin is also considered as a luteotropic factor during pregnancy and the second phase of the luteal stage. Treatment is effective during the anestrous phase of the cycle and is still effective even though anestrus in bitches do not have prolactin secretion.

It is assumed that regular gonadotroph secretion is the underlying cause of the clinical success because the induced estrus cycles are fertile and regular and are associated with follicular growth and ovulation. It can be indirectly demonstrated that the G&I-I production in the hypothalamus and FSH production in the anterior pituitary gland are elevated during the treatment. This assumed effect is rarely seen in prolactinaemic conditions, e.g., during pseudopregnant lactation since in these cases estrus is seen only very sporadically.

Even though the treatment has been successful in most cases, bromocryptine mode of action in estrus induction is not known precisely. Further hormonal profiles are needed to determine treatment duration schedules, dose rates and mode of action in the regulation of the sexual cycle in bitches.

Surgical intervention

Not only pharmaceutical measures can be taken to prevent estrus in the dog. Surgical intervention by removal of the ovaries (ovariectomy) and the uterus (hysterectomy) can be performed. These procedures will provide a 100% success rate in preventing pregnancy but does come with an array of side effects and possible complications.

While these interventions are common and performed frequently in several countries, other countries may be in less favor of the procedure. Norway for instance, demand by law a medical or welfare reason for neutering domestic pets (Mattilsynet, 2015). In the U.S. it is the other way around – unless the dog is used for breeding it should be spayed (AVMA). Here gonadectomy, referred to as early-age neutering, the animal is neutered as young as in the seventh week of life. This has shown to reduce morbidity as well as a speedier recovery. The adverse effects from this early form of neutering appear to be the same as in neutering of adults (Olson and Kustriz, 2001).

Physiological alterations caused by hormone therapy

The use of naturally occurring or synthetic hormones may have side effects and cause physiological alterations. Some examples are Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate and Exogenous estrogens. Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate contains the hormone progestin. It is not approved for canine contraception in all countries, as it may cause complications such as diabetes, pyometra, and acromegaly. It also significantly increase the risk of mammary hyperstimulation, leading to mammary nodules and mammary cancer (Concannon, P.W., 2010).

In female dogs, estrogens or synthetic estrogenic compounds have been used in the treatment of estrus induction for decades. Estrogen is a steroid compound, primarily synthesized by the ovaries (Sontas et al , 2009). The most common reason for the use of estrogens in small animal practice, is the immediate treatment of unwanted matings. The estrogens will prevent conception by the closure of the tubal-uterine junction or their effect on the oviduct and uterus.

Today, the use of estrogens for mismating is no longer recommended because the development of estrogen-induced myelotoxicity (EIM) and pyometra following the use of estrogens for the management of diseases and for experimental purposes has been reported. There are no safe and efficacious doses of estrogens existing, and most mismated dogs are reported to be nonpregnant at the time of examination. EIM can show clinical signs which may include complete loss of appetite, uni- or bi-lateral epistaxis ,depression, petechial hemorrhages, vulvar edema, pale mucous membranes and vaginal bleeding. For hematologic changes the most typical ones are nonregenerative anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis followed by a leukopenia (Sontas et al, 2009.).

Different aspects of manipulation

The direct effect of progestins in regards the gonadotropin levels in dogs are disputed. Side effects of progesterone treatments has also seen variation with manufacturer. The common contradiction for them all however is to avoid treatment in bitches who has a potential for reproduction. This is due to the risk that the estrus will not return after treatment, especially if the treatment is provided over a longer period. However, this is a small risk (~3%) and, in most cases, fertility will not be heavily affected once the progesterone treatment is suspended. Side effects may include weight gain and lethargy as well as changes in behavior and alterations to the endometrial lining of the uterus. It can also provide a diabetogenic effect along with several other severe endocrine hypo- and hyperfunctions.

For prepubertal and pregnant bitches neither synthetic progesterone nor androgens should be used as progesterone has a significant effect on the cervix. This lastly mentioned effect therefore also affects bitches with a history of uterine diseases, diabetes mellitus or mammary tumors. Progesterone being a steroid compound will therefore metabolize in the liver. Due to this fact, bitches with underlying or predisposed hepatic conditions should refrain from receiving this form of treatment.

Summary

Being aware of the benefits as well as the difficulties and complications of this form of manipulation is crucial in the veterinary field. The request to neuter pets may alter in popularity throughout the world, but it will impact the overall health of the pet regardless. Considering the overall welfare of the animal and its health condition should always be executed prior to any form of manipulation. Behavioral therapy in case of unwanted conduct is still necessary if this was the primary cause of intervention. Thorough examinations of liver conditions, pancreas, female genital tracts and thyroid function should be performed in advance and have a significant influence on the treatment choice.

Studying the above we can find several alternatives for altering the estrus cycle in the bitch. Some methods have shown to be more secure than others and, in some cases, a necessity to stray from overpopulation. Several side-effects can be observed regardless of pharmaceutical or hormonal intervention, some known and some yet to be clarified. One should however refrain from manipulating the hormone cycle as far as possible.

Literature

American veterinary medicine organization https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/elective-spaying-and-neutering-pets

Concannon, P.W. (2010): Reproductive cycles of the domestic bitch. Animal Reproduction Science 124: (3-4) 200-10 http://physioweb.vet-alfort.fr/Documents/Pdf/Reproduction/Concannon10_BitchCycleReview.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3_7IAaf0lKoMOkVxTphchywJblvFjlNQ2gHe2sUx7JUm1AB1EsdNLK-C4

Cooper, W.; Larsen (2006). Immunocontraception for mammalian wildlife: ecological and immunogenetic issues. Society of Reproduction and Fertility 132: (6) 821-828

Dyce (2010). Veterinary anatomy by Saunders 4: 197

Kutzler (2018). Estrous cycle-manipulation in dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 48: (4) 581-594

Maenhoudt, R. Santos, Fontbonne (2018), Manipulation of the estrous cycle in the bitch – What works for now. Reproduction Domestic Animals 53: (3) 44-52 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/rda.13364

Mattilsynet, Statens tilsyn for planter, fisk og næringsmidler https://www.mattilsynet.no/dyr_og_dyrehold/kjaledyr_og_konkurransedyr/hund/kastrering_av_hund__er_det_tillatt.13955

Olson PN.; Kustritz MV.; Johnston SD.; (2001): Early-age neutering of dogs and cats in the United States (a review) Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. Supplement 57: 223-32.

Sontas.; Dokuzeylu; Turna; Ekic (2009): Estrogen-induced myelotoxicity in dogs: A review. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 50: (10) 1954-1058 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2748286/?fbclid=IwAR3ZSdVLfADU3sgkg_WoEVrz9pvCTv0JqSqtRlXlAHX8F6qTIjtUwusYyo8

Zöldág L.; Fekete, S.; Csáky; Bersényi; (2000): Fertile estrus induced in bitches by Bromocryptine, a dopamine agonist: a clinical trial. Theriogenology 55: (8) 1657-1666

Figures

Figure 1 - Self drawn picture (notability) of the monoestrous cycle in the bitch

Figure 2 - Self drawn picture (notability) of hormonal changes during estrous cycle in the bitch