|

Size: 18759

Comment:

|

Size: 19229

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 15: | Line 15: |

=== The Foot of the Camel === ||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:right;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em;"> {{attachment:camelsfoot.jpg|Diagram of the structure of the foot of a camel|width="350"}} || |

||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:right;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em;"> {{attachment:camelsfoot.jpg|Diagram of the structure of the foot of a camel|width="350"}} || |

| Line 21: | Line 19: |

=== The Foot of the Camel === |

|

| Line 30: | Line 31: |

| <<BR>> ||<tablebgcolor="#eeeeee" tablestyle="float:left;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em;"> {{https://ayushmaanroy.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/wp-1458845288413.jpeg?w=756|Camel red blood cells side by side with human red blood cells|width="250"}} || ||'''Figure 2. '''''Camel red blood cells compared''<<BR>>''to human red blood cells (Roy, 2016)'' || |

|

| Line 31: | Line 39: |

| * They have oval shaped red blood cell that are a light-red color. * The elliptical shape of the red blood cell is believed to facilitate blood flow even in a dehydrated state. * Volume of plasma may be slightly reduced in periods of high dehydration. |

. They have oval shaped red blood cell that are a light-red color. <<BR>> . The elliptical shape of the red blood cell is believed to facilitate blood flow even in a dehydrated state. <<BR>> . Volume of plasma may be slightly reduced in periods of high dehydration. <<BR>> <<BR>> <<BR>> |

| Line 84: | Line 94: |

| ||<tablebgcolor="# eeeeee" tablestyle="float:center;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em; ;text-align:center"> {{https://www.physiology.org/na101/home/literatum/publisher/physio/journals/content/physiologyonline/2014/physiologyonline.2014.29.issue-3/physiol.00049.2013/production/images/medium/phy0021402030003.jpeg}} <<BR>> ''' Figure 2. ''<<BR>>'''''The SBC in action in conditions of dehydration vs euhydration in camelids (Fuller, 2014)'' ''' ''''' || | ||<tablebgcolor="# eeeeee" tablestyle="float:center;font-size:0.85em;margin:0 0 0 0; "style="padding:0.5em; ;text-align:center"> {{https://www.physiology.org/na101/home/literatum/publisher/physio/journals/content/physiologyonline/2014/physiologyonline.2014.29.issue-3/physiol.00049.2013/production/images/medium/phy0021402030003.jpeg}} <<BR>> ''' Figure 2. ''<<BR>>'''''The SBC in action in conditions of dehydration vs euhydration in camelids (Fuller, 2014)'' ''' ''''' || |

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BEHAVIOURAL ADAPTATION OF CAMELS FOR HEAT REGULATION, WATER METABOLISM, AND DESERT SURVIVAL

Y Ramcharan, N Alkhalifa and Z Z Rizvi

Contents

- PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BEHAVIOURAL ADAPTATION OF CAMELS FOR HEAT REGULATION, WATER METABOLISM, AND DESERT SURVIVAL

Introduction

Regardless of camels being highly associated with the Middle east and Africa, they originated from North America about 45 million years ago (Cohen, 2013) and from there on have migrated great distances. The family of camelids consists of: of the Dromedary, also known as the Arabian camel, which is single humped; the Bactrian which is double humped; the Alpaca, the Llama, the Vicuna, and the Guanaco. All species of the camel can be traced back to the specie of even toed ungulates called the Artiodactyl, and the suborder Tylopoda. Camelids play a crucial role in the life of the ancient Arabs who lived in the desert: the camel's physiology matched perfectly to their harsh days and they ideally suited their lives habitually and traveling-wise. The camel stayed side by side with the desert peoples’ lives, resistant and generous in tough, dry, and poor conditions, until the modern ways of transportation were invented. People relied on them for the sake of transport of heavy materials from one area to another, and they were also used for riding through long distances, nutritional reasons (for example camel hides, meat, skins, and furs) and for entertainment purposes, such as racing for leisure. Camels have proven to be the perfect desert animal due to their high production of meat and milk compared to any other animal living in said environment. (El Amin, 1979).

Goal of the Research: To shine a light upon the camel’s fascinating abilities in accomodation to—and survival in—extreme arid climates.

Physiology of Accommodation:

|

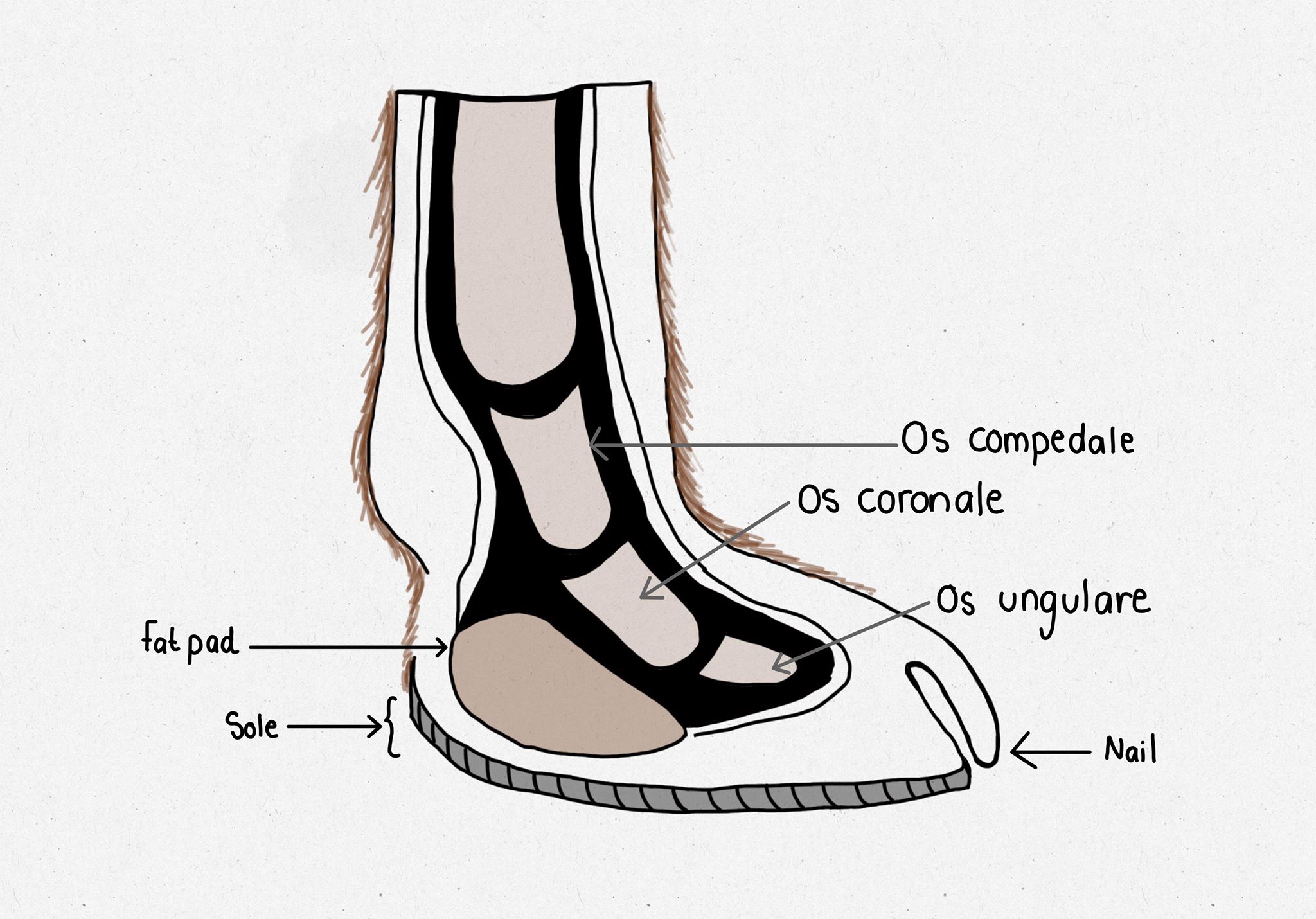

Figure 1. Simplified diagram of the foot of a camel |

The Foot of the Camel

- The feet of the camel are not hooved, like most ruminants' would be, but instead consist of two nailed digits.

- Each foot flattens and spreads when the animal applies its body weight on it, thus stopping the animal from sinking into the dense hot sand.

- Camels have thick fat-padded soles which also act as protection against extreme temperatures.

The Camel's Hump

- The hump consists of a large store of fat within connective tissue with the absence of water.

- In the presence of oxygen, the fat is thereby metabolized into water and energy.

- The fat content of the camel hump depends on the animal’s age: the older the animal, the larger the fat content.

|

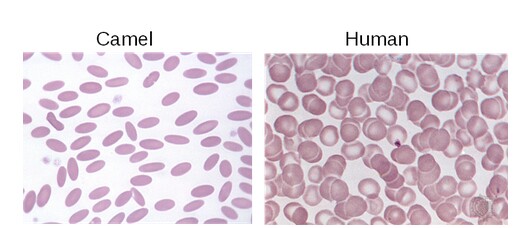

Figure 2. Camel red blood cells compared |

The Blood of the Camel

They have oval shaped red blood cell that are a light-red color.

The elliptical shape of the red blood cell is believed to facilitate blood flow even in a dehydrated state.

- Volume of plasma may be slightly reduced in periods of high dehydration.

The Udder

- The udder is in the groin area, and does not reach the ground.

- The nipple contains 3-2 openings. Within each nipple there are two storage areas of milk.

- There are glands in the nipple that protect it from bacteria and further infection.

The Urinary System

- The skeletal tissue in the kidney is four times larger than the tissue of the cortex, to allow as much water to be returned to the body as possible.

The Digestive System

- The upper lip is lean and strong, split in the middle, while the lower lip is lean and soft.

- They have 22 deciduous teeth, but their permanent teeth consist of 34 teeth with no upper incisors

- Their pharyngeal cavity is covered with a mucosal layer and is rich in mucosal glands, which eases dry and spiky food to glide easily into the esophagus.

- The camel is a pseudo-ruminant, meaning the stomach consists of three cavities: the rumen, the reticulum, and the abomasum; which help in storing plants poor in protein for up to three days to add to the protein that is made from urea.

- The length of the camelid intestines is 45 meters and can contain 145 litres.

- The liver does not have an accompanying gallbladder.

Water Consumption

- A thirsty camel can drink 120 liters of fresh or brackish water in one go regardless of saltiness. It can also drink a third of its weight, 200 liters, in two minutes.

Respiratory System

- The number of breaths per minute is decreased in order not to lose water, which is around 10-8 breaths per minute in comparison to cattle, which is 25 breaths per minute.

- The nostrils are small in comparison to the body, supplied with layers of strong muscular tissue that can control the opening and closing of the nostrils, while the nostrils additionally are embedded with mucosal coverings to better ventilate the air passing through.

Skin/Coat

- The skin can stretch and shrink, specific to the hump area.

- The skin of the body is thick.

- The skin of the camel's toes does not tear and also does not get replaced in the entirety of a camel's life.

- The sweat glands do not work consistently; only 2 to 3 hours during the day to minimize water loss.

The Eye

- The eye is small comparably, but bright and clear, resulting in a great sense of sight and the ability to journey through the night without losing orientation.

- The orbital cavity is isolated by two layers of bones to better ventilate the air.

- The lacrimal glands are very active, always secreting fluid onto the eyes to maintains their clarity through dusty environments.

- The eyelids are strongly supportive and large to protect the eye from billowing sand.

Skeleton

- The limbs are very long which aids in taking wider steps for larger distances, in addition it helps in regulating body temperature exchange from the limbs to the body.

- The neck is very long for grazing on large trees with high-up branches, such as the acacia.

- The bones are strong and large, providing a sturdy frame for the mammal that will not collapse easily under duress.

Grazing Habits

- Camels tend to graze on plants low in fiber but high in protein and water.

( الزروقي ومدني ،1992 )

Heat Regulation

This is the ability of the camel’s internal body temperature to change drastically but still maintain homeostasis. They can cope with extremely hot days and very cold nights in the Arabian desert. Camels are heterothermic animals, depending on the light-cycle and also on the ambient temperature. During dehydration , the animal becomes poikilothermic. It must be noted that variation in body surface temperature and skin temperature is higher in the hump area compared to the underarm and flank areas. During the day, the camel stores the heat energy produced throughout the hot days, which is then used for warmth during the cold nights. Heat regulation depends exclusively on evaporation on the body surface and not on increasing respiratory rate or panting which are absent in camelids.The fur of the camel is an efficient barrier against heat gain from the environment. As investigated by Fuller et al (2014) during heat stress, the camel will initiate selective brain cooling (SBC) since the brain consists of extremely sensitive tissues. This is done by the diversion of blood cooled by the nasal cavities which travel to the brain sinuses. In this way, venous blood cools down arterial blood of the carotid rete. This mechanism occurs during temperature changes of 33-45°C. It can thereby be concluded that myogenic vasoactive mechanism is the major means to heat regulation. (Elkhawad, 1992)

Figure 2.

The SBC in action in conditions of dehydration vs euhydration in camelids (Fuller, 2014)

Water Preservation and Sweat Glands

The camel can tolerate water loss up to 30% of its body weight as compared to common mammals who can tolerate only 12% water loss. It must be noted that camels do not lose their appetite during dehydration unless extreme dehydration levels have been reached. It has been observed that when dehydrated camels are presented with water, they ingest a larger volume compared to the volume lost. Camels sweat directly from the skin surface as opposed to the hair surface since the former is much more effective and efficient, so uses less energy. The excess water will be excreted 2-4 days later. Furthermore , the camel can drink one third of its body weight in water within 10 minutes without becoming intoxicated. In case of dehydration and high ambient temperatures, camels reduce their fecal, urinary and sweat production. During dehydration periods, the kidneys reduce water loss both by decreasing the glomerular filtration rate and by increasing the tubular reabsorption of water. Lastly, their ability of regulating their body temperatures from 34.5-40.7°C conserves a lot of water when most needed (Kataria et al., 2001 A).

Kidney Function and Water Metabolism

The kidneys play a crucial role in the process of water balance inside the body, but they are not the only responsible organ for water excretion. The lungs, the skin and the digestive system also participate in this process. It has been proven that the camel can go for up to three days from water consumed through greenery present, and the amount that can be consumed by a camelid from plants is approximately around 30 liters per day. During the colder months, the camel does not require to, and so does not drink large amounts of water. Water consumption is dependent on the weather temperature during the respective season, the activity of the animal, and the amount of water present in the feed. Several studies have deduced that camels can go 30 days and a distance of 6000 kilometers without the present of water (Yagil et al.,1983.)

During the consumption of water, the absorption occurs in the mouth and the glands due to the drinking receptors being present inside the mouth which get activated once water has entered the mouth. Absorption also continues in the stomach and the intestines. The camel does not rely on water production from metabolic process, especially in the cases of extreme thirst, to avoid the additonal heat production that occurs inevitably during these processes (Havez, 1968.)

The function of the kidney is absorbing as much as water so it can be returned into the body. In account to the amount of urine excreted in a thirsty camel is 0.001 of the camel’s weight per day while in thirsty goats it is 0.005 of their body weight per day which 5 times more of their body weight in comparison to the camel. The urine excreted in the camel is highly concentrated which is due to the anatomical feature of the kidneys having a high number of nephrons with longer loops of Henle in comparison to other animals, the longer length helps in a higher water absorption into the bloodstream. Studies have shown that the amount of water excreted by the urine decreases from 5 liters to 1.5 liters per day in the state of thirst. In addition to that it has been shown that the glomerular filtration rate decreased in the situation of lack of water by 75%, meaning from 81 mL per kg to 22 mL per kg, and the amount of blood plasma into the kidney by 72%. Not only that, but the camel also possesses the ability to change concentration of its urine, due to the kidneys' response to antidiuretic hormone (Yagil, 1974).

Furthermore, the camelid kidney is said to have higher amount of salt in the produced urine than of sea water when the camel’s diet is mainly salty plants. The antidiuretic hormone is produced in the hypothalamus and then released into the bloodstream in response to increased levels of osmolarity.

Water Metabolism in Stomach and Intestines

The first compartment comprises 83% of the total stomach volume and is analogous to the rumen. The second compartment is analogous to the reticulum and contains 6/10 of the total gastric volume. The mucosal surface exhibits a retiform pattern composed of absorptive cells and mucous glands. The third compartment is the abomasum counterpart of the camel’s stomach. (L. R. Esteban et. L. R. Thompson, 1988) The camel in comparison to the cow can withstand three weeks with no water without losing its appetite, while the cow can only withstand 3 days before losing its appetite (البشير ،1998 Al Basheer).

Salivary Glands and Water Metabolism

When compared to the salivary glands of other ruminants (Mursal, 2016) those of camels show a few key differences as opposed to their counterparts of oxen, goats, and sheep. With the parotid salivary gland partially covered by the parotidoauricularis muscle and the mandibular salivary gland opening into the oral cavity via a mucosal fold (and not the regular sublingual caruncle) already changes in physiology can be seen across the species.

Though the true structure of the glands in question in conclusion resemble those of bovines (Mansouri, 1994) it has been shown that those in camels are hyperdeveloped, in order to regulate salivary secretion (it is continuous) in a way that would prevent the need for excess water consumption due to parchedness of the mouth.

Conclusion

References

Bibliography

Arabic References:

- (Al Basheer البشير ، عمر مساعد . الخصائص الفسيولوجية للإبل ، رسالة ماجستير جـامعة أم درمان الإسلامية (1998

- (الزروقي السنوسي ومدني محمد خصائص الإبل وحيدة السنام – معهد الإنماء العربي الجمهورية العربية الليبية – طرابلس (1992

English References:

Al-Baka, H. A. (2016). Camels and adaptation to water lack. MRVSA,(5), 64-69.

Ali, M. A., Adem, A., Chandranath, I. S., Benedict, S., Pathan, J. Y., Nagelkerke, N., . . . Kazzam, E. (2012). Responses to Dehydration in the One-Humped Camel and Effects of Blocking the Renin- Angiotensin System. PLoS ONE,7(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037299

Banerjee, S., & Bhattacharjee, R. C. (1963). Distribution of body water in the camel (Camelus dromedarius) [Abstract]. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content,204(6), 1045-1047. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.6.1045

Bouâouda, H., Achâaban, M. R., Ouassat, M., Oukassou, M., Piro, M., Challet, E., . . . Pévet, P. (2014). Daily regulation of body temperature rhythm in the camel (Camelus dromedarius) exposed to experimental desert conditions. Physiological Reports,2(9). doi:10.14814/phy2.12151

Cohen, J. (2013, March 05). Giant Ancient Camel Roamed the Arctic. Retrieved April 24, 2019, from https://www.history.com/news/giant-ancient-camel-roamed-the-arctic

Elkhawad, A. (1992). Selective brain cooling in desert animals: The camel (Camelus dromedarius) [Abstract]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology, 101(2), 195-201. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(92)90522-r

Esteban, L. R., & Thompson, J. R. (1988). The Digestive System of New World Camelids - Common Digestive Diseases of Llamas. Iowa State University Veterinarian, 50(2), Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastate_veterinarian/vol50/iss2/9.

Fuller, A., Hetem, R. S., Maloney, S. K., & Mitchell, D. (2014). Adaptation to Heat and Water Shortage in Large, Arid-Zone Mammals. Physiology,29(3), 159-167. doi:10.1152/physiol.00049.2013

Ghoke, S. S., Jadhav, K. M., & Thorat, K. S. (2013). Assessing the Osmotic fragility of Erythrocytes of rural and semiurban Camels ( Camelus dromedarius ). Camel- International Journal of Veterinary Science,1(1), 75-78.

Haroun, E. (1994). Normal concentrations of some blood constituents in young Najdi camels (Camelus dromedarius). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology,108(4), 619-622. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(94)90347-6

Mansouri, S. H., & Atri, A. (1994). Ultrastructure of Parotid and Mandibular Glands of Camel (Camelus dromedarius). Journal of Applied Animal Research,6(2), 131-141. doi:10.1080/09712119.1994.9706035

Mursal, Mohammed, N. J., Ahmed, H. A., & Hassan, Z. (2016, March 13). Comparative Morphological, Histometric and Histochemical studies of Parotid and Mandibular Salivary Glands of Camel, Ox, Sheep and Goat. Retrieved from http://repository.sustech.edu/handle/123456789/14195

Nejat, S., Pirmoradian, M., Rashedi, M., & Nejat, S. (2016). Prevalence rate and composition of bladder stones in camel (Camelus dromedarius). Journal of Camel Practice and Research,23(1), 147. doi:10.5958/2277-8934.2016.00024.2

Schmidt-Nielsen, B., Schmidt-Nielsen, K., Houpt, T. R., & Jarnum, S. A. (1956). Water Balance of the Camel [Abstract]. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content,185(1), 185-194. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.185.1.185

Schmidt-Nielsen, B., Schmidt-Nielsen, K., Houpt, T. R., & Jarnum, S. A. (1957). Urea Excretion in the Camel [Abstract]. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content,188(3), 477-484. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.188.3.477

Schmidt-Nielsen, K., Schmidt-Nielsen, B., Jarnum, S. A., & Houpt, T. R. (1956). Body Temperature of the Camel and Its Relation to Water Economy [Abstract]. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content,188(1), 103-112. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.188.1.103

Solaiman, M. K. (2015). Functional Anatomical Adaptations of Dromedary (Camelus Dromedaries) and Ecological Evolutionary Impacts in KSA. International Conference on Plant, Marine and Environmental Sciences (PMES-2015) Jan. 1-2, 2015 Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia). doi:10.15242/iicbe.c0115058

Stone, H. O., Thompson, H. K., Jr., & Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1968). Influence of erythrocytes on blood viscosity. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content,214(4), 913-918. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.214.4.913

Yagil, R.; Etzion, Z.; Oren, A. (1977). Camel thyroid metabolism: Effect of season and dehydration: J. App. Physiol. 421: 680-683