THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF EATING DISORDERS (ANOREXIA NERVOSA, BULIMIA NERVOSA), AND THE ROLE OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL (INDIVIDUAL, FAMILIAL) FACTORS

Eating disorders, such as Anorexia Nervosa (AN) and Bulimia Nervosa (BN), are growing in prevalence amongst today’s societies. With origins in psychological disturbances, the pathophysiological effects of the diseases have far reaching consequences on the physiological processes of the body. As defined in DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), Anorexia Nervosa is a constant attempt to maintain a body weight below the minimal normal weight (85%), or maintain a body mass index lower than 17.5 for age and height. It is accompanied by an intense fear of weight gain and an inaccurate perception of the person’s own body size, shape, or weight. The DSM-IV also defines Bulimia Nervosa as repetitive episodes of binge eating followed by the repetitive purging of food, excessive exercising, or prolonged fasting at least two times per week for three months. It is also generally associated with an excessive concern about weight or shape (Rikani et al, 2013). Both AN and BN are dangerous diseases, affecting multiple organ systems, such as skeletal bones, linear growth, brain development, and fertility functions. AN is a recognised life-threatening disorder, with a significant risk for sudden death (5 to 20%) due to severe cardiovascular complications (Yahalom et al, 2013). While this essay explores the different pathophysiological effects these eating disorders have on the body, it places a particular emphasis on the cardiovascular complications such as Bradycardia and ECG abnormalities, as they occur in up to 80% of patients with AN, and account for up to 30% of mortality (Kalla et al, 2017). Before these effects can it be outlined it is important to highlight the disorders’ psychological origins to better understand its prevalence, amongst young adults in particular.

Contents

Psychological Factors

It has been clear from studies that although psychological factors (individual vulnerability or family influence) may not solely cause AN or BN, they certainly play a major role in the onset of eating disorders (EDs) in early adolescents, especially among females (Tafa et al, 2017). A common characteristic of the family unit that AN sufferers are often part of, is that they have previously lost a family member (Wozniak et al, 2012). We can draw the conclusion that the role of a family member death can cause the extreme and unique sadness felt by the family, which is known to influence the onset of the disease, as unique patterns of expressed emotion (EE) is found to characterize families of adolescents with AN/BN (Rienecke et al., 2016). Of course other factors can have a role in initiating unique patterns of EE within the family, for example: cases of depression, alcoholism and eating disorders suffered by parents or other family members (Wozniak et al, 2012) Another one of these triggers may be parental expressed emotion, for example: family status, dealing with the relationships between the parents or between the parents and children (Rienecke et al, 2016). The studies of Rienecke et al. (2016) further concluded that the relationship between father and child and mother and child have been known to affect which variation of the eating disorder becomes present. It has been found that both mothers and fathers were significantly more critical of patients with BN than they were toward patients with AN. In addition, parents of AN/BN sufferers are said to be over-protective or alternatively be poorly involved with their children; or to be likely to avoid conflicts or alternatively show a rigid functioning (Tafa et al., 2017). It is interesting to note that a fast-paced, modern lifestyle is greatly affecting relationships between family members, as it wears out family bonds and reduces the time spent between parents and children. New priorities are being set, ones that are altered significantly from those of previous generations (Wozniak et al, 2012). Furthermore, during adolescence, as the brain and cognitive functions are maturing and the relationships with peers gain a central role and a reorganisation of family functioning takes place (Tafa et al, 2017). Therefore, both of these have an indirect role in the development of AN/BN. In conclusion, we can see why therapists treating adolescents with eating disorders should assess for parental EE and provide appropriate interventions to reduce high EE when possible (Rienecke et al, 2016).

Another factor of psychological origin which has a role in the development of AN/BN is the individual’s own thoughts. These can be influenced and altered by a number of experiences, mostly traumatic, as it has been found that increased emotional disturbance during adolescence may increase the likelihood of suffering from an eating disorder (Tafa et al, 2017). One of these disturbances is sexual abuse, as studies show that as many as 1 in 3 anorexic patients have been sexually abused during childhood. Anorexic patients have shown common characteristics with sexual abused victims, such as low self-confidence, feelings of shame and a negative attitude towards their body (Wozniak et al, 2012).The lack of confidence and its role in the patients vulnerability to the diseases may then be reinforced further by modern day society and the influence it has over young people these days. The media, which is image obsessed, promotes the idea that success can only be achieved by looks and undermines educational, cultural, and social values (Wozniak et al, 2012). Another conclusion drawn is that the need for independence in adolescent life acts as an internal factor contributing to the development of these dangerous disorders (Wozniak et al, 2012).

General Pathophysiological Effects

The general pathophysiological effects of AN and BN have many similarities but also differ in many cases, for example the laxative and induced vomiting as seen in BN, and the very low body mass and severe malnutrition in AN (Rikani et al, 2013). Almost every body system can be adversely affected by the state of progressive malnutrition induced by these disorders. Both diseases affect a wide variety of bodily functions. Some effects can be permanent, but fortunately, many of these adverse effects can be reversed with weight gain and nutritional rehabilitation. AN has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder due to many of these effects listed in Table 1 below (Mehler and Brown, 2015).

General Effects

Medical Complication

Anorexia Nervosa

Bulimia Nervosa

Dermatological

• Dry skin that may fissure and bleed from fingers and toes

• Cold intolerance/discolouration of extremities known as acrocyanosis, which can be due to hypothermia, causing shunting of blood flow centrally

• Lanugo hair – to conserve heat

• Decubitus ulcers and bruising – results in loss of supporting subcutaneous tissue caused by weight loss• Skin abrasions and callous of knuckles/hands by inducing the gag reflex (Russel’s sign)

• Alopecia

• Xerosis

• Hypertrichosis

• Lanuginose

• Cheliosis

• Carotenoderma

• Pruritis

• Nail fragilityGastrointestinal

• Delayed stomach emptying and bloating, upper quadrant pain and early satiety which can cause gastric necrosis

• Constipation by reduced calorie intake causing reflex hypofunction or slow colon transit

• Liver - Liver transaminases (AST & ALT) are often abnormal in anorexia nervosa – higher (dextrose)

• Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMA) - compression of the duodenum between the aorta and spine due to loss of adipose tissue on SMA

• Disphagia - Aspiration caused by muscle weakness of pharynx

• Acute pancreatic – Elevation of lipase and amylaseGastroparesis–Delayed stomach emptying and bloating, upper quadrant pain and early satiety which can cause gastric necrosis

• Constipation by reduced calorie intake causing reflex hypofunction or slow colon transit"

• Liver - Liver transaminases (AST & ALT) are often abnormal in anorexia nervosa – higher (dextrose)

• Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMA) - compression of the duodenum between the aorta and spine due to loss of adipose tissue on SMA

• Disphagia - Aspiration caused by muscle weakness of pharynx

• Acute pancreatic – Elevation of lipase and amylase• Many effects on the gastrointestinal tract due to continuous abnormal exposure of acidic gastric juice

• Oral cavity - one of the first obvious signs of BN

• Dental erosion

• Reduced salivary flow rate

• Tooth hypersensitivity

• Dental caries

• Periodontal disease

• Xerostomi

• Hypertrophy of the salivary glands

• Laryngopharangeal Reflux - esophageal sphincters/larynx and pharynx damage

• Throat irritation

• Esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus

• Boerhaave’s syndrome (esophageal rupture)- rare medical emergency

• Melanosis coli, cathartic colon, and functional impairmentEndocrine

• Cortisol ↑ Growth hormone ↑

• IGF ↓ ADH ↓

• Thyroid - Euthyroid sick syndrome: T3 and T4 ↓

• TSH= Normal (Normalize with refeeding)

• Hypoglycemia: Decreased glycogen stores (can cause live failure)

• Hyperglycemia Diabetes: Premature microvascular complications -Diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy

• Sex hormones (GnRH) ↓

• GnRH, LH, FS, estrogen and testosterone↓ – effects potency, fertility and bone density

• Hypothalamic amenorrhea syndrome

• Infertility due amenorrhea and decreased libido. Conception becomes difficult• Pseudo-Bartter’s syndrome

• Irregular renin-angiotensin-aldosterone steroid hormone system – may cause dehydration and low serum potassium levels

• Electrolyte imbalance and alkalosis may appearHematologic

• Bone marrow adverse effects - red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets

• Hypoplastic marrow with gelatinous deposition and serous fat atrophy

• Anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (less common)

• As disease progresses-cytopenia

• Neutropenia , lymphopenia – White blood cells proportionally reduced

• Serum international normalized ratio (INR) level slightly increased leading to petechiae, purpura - liver damage and coagulation factors impaired synthesis• Hypokalemia

• Hyponatremia

• Hypomagnesiemia (caused by diarrhoea)

• Hypocalcaemia

• Metabolic alkalosis (in case of severe purging)

• Metabolic acidosis (in case of severe laxative abuse)Neurologic

• Brain atrophy

• Similar to brain of Alzheimer’s on MRI scan

• Ventricle enlargement and cortical substance decreasedBonemetabolism

• Bone structure impairment and bone strength reduced

• Osteoporosis or osteopenia

• Increased bone resorption

• Estrogen deficiency → ubiquitous hypogonadotropic hypogonadismCardiac

• Bradycardia and hypotension

• Tachycardia – very rare and unusual

• Heightened vagal tone-> suggested as the cause of bradycardia for anorexia

• Structural abnormalities, including pericardial effusion and decreased left ventricular size

• Pericardial effusion

• Due to longstanding hypovolemia- decreased left ventricular mass, left ventricular index, cardiac output, and left ventricular diastolic and systolic dimensions

• Mitral valve motion abnormalities

• Subtle arrhythmias – cardiac failure• Tachycardia - torsades de pointes (fatal)

• Hypotension

• Orthostasis

• Prolonged QTc interval- risk for significant arrhythmias

• Abuse of Ipecac (vomiting stimulant) may result in cardiac myocyte damage causing in heart failurePulmonary

• Emphysema

• Diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and lung diffusion capacity for oxygen decreased

• Pneumothorax/pneumoperitoneum by acute gastric rupture

• Pneumomediastinum (rare)• Aspiration of regurgitated food

• Respiratory distress

• Lower lobe opacities

• Pneumomediastinum = dissection of air through the alveolar wallsTable 1: Information based on articles by Mehler and Brown (2015) and Rikani et al, (2013)

Cardiological Effects

ECG Abnormalities

|

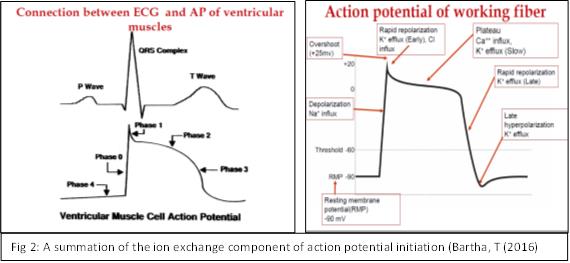

The process of Electrocardiography (ECG) can measure the summation of the activity of all cardiac muscle fibres together, giving an overall picture of the heart functioning (Fig.1). By comparing the ECG of a healthy individual and one suffering from an eating disorder, the detrimental cardiac effects can be visibly examined. An extreme or rapid loss of weight can cause changes in both depolarization and repolarization (Vedel-Larsen et al, 2016). The many studies carried out on this pathophysiological effect have yielded issues with the QRS complex in particular. This complex marks the beginning of ventricular depolarization. The R-wave reflects the maximal ventricular depolarization, therefore changes in its amplitude has been established as a marker of cardiac risk, even outside the realm of eating disorders (Green et al, 2016). Studies suggest that women with eating disorders such as AN/BN showed a notable decrease in mean R wave amplitude compared to that of a healthy control, suggesting a decreased contractile force and significant disruption in cardiac signalling (Green et al, 2016). In their article, Green et al (2016) further remark that their findings may be explained by the impact of the disorders on physiological indices which affect cardiac function, such as:

"i." Excessive exercise and other purge behaviours can cause an autonomic shift that results in a disruption of cardiac signalling because of hypervagal tone

"ii." Behaviours such as fluid restriction, self-induced vomiting, and laxative and diuretic abuse cause significant dehydration, which leads to a decrease in venous return and intracavity blood volume

"iii." aberrant cardiac signalling from electrolyte disturbances

"iv." a protein-energy imbalance resulting in decreased left ventricular mass and wall thickness

It is widely debated that the main cause of sudden cardiac death in the AN population is as a result of the QT prolongation (Kalla et al, 2017). The reported prevalence varies greatly, but up to 25% of AN patients are thought to manifest QT prolongation, with a significant proportion of these fatalities occurring as a consequence of ventricular arrhythmias secondary to an acquired long-QT syndrome (Padfield et al, 2016). According to Vedel-Larsen et al (2016), it is widely accepted that a prolonged cardiac QT interval is associated with an increased risk of torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia (TdP), a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia condition that can easily degenerate into lethal arrhythmias. Therefore, the QT interval is recognised as an important parameter when assessing arrhythmic risk. They argue that both hypo- and hyperglycaemia have been associated with blocking the HERG potassium channels, indicating that disruption in glycaemic levels can effect cardiac repolarization. The electrolyte concentration is essential for eliciting an action potential within the cardiac muscle, as the ion exchange between the two sides of the membrane leads to the electrical changes in the excitable tissue (Fig.2).

|

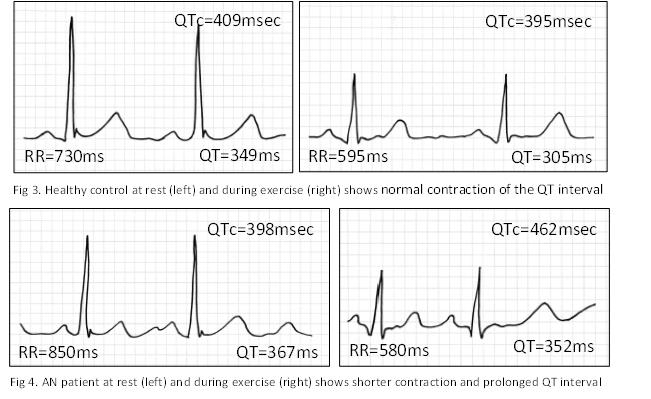

Blocking the potassium channels prevents the early, slow and late potassium (K+) efflux that determines normal repolarization, drawing out the process and having a significant negative impact on the cycle as a whole. Exercise testing between AN patients and healthy controls easily demonstrates an impaired repolarization, even without the presence of overt resting QT prolongation (Fig. 3-4). From the results it is clear that AN causes a flattening of the QT/RR slope. Figure 3 shows a normal contraction of the QT interval by ≈45 msec in response to an increase in heart rate of 20 beats/min in a healthy control. The QTc shortens from 409 msec to 395 msec in Figure 4 (AN patient), despite a larger increase of 30 beats/min. Here the QT only contracts by 15 ms but the QTc paradoxically prolongs from 398 ms to 462 ms (Padfield et al, 2016).

|

Bradycardia

The prevalence of cardiac arrhythmia is very commonly seen as a side effect from eating disorders. Cardiac complications, especially tachycardia and bradycardia, can be observed, but sinus bradycardia has been shown to be the most common arrhythmia and cardiovascular physical finding. Sinus bradycardia is “presumably an effect of vagal hyperactivity, which subsequently decreases the cardiac output” (Meczekalski et al, 2013). AN has one of the highest mortality rates of all psychological disorders, which can be mainly due to the sudden unexpected cardiac arrhythmic death. Yahalom et al (2013) defined bradycardia as a heart rate lower than 50bpm during the day time, and lower that 45bpm during the night time. Bradycardia may be a response to continuous and drastic weight loss and negative energy balance. In anorexia patients, it is rare to observe tachycardia, with heart rates between 80-90 bpm being highly unusual and may suggest a superimposed infection or other complication. Suggestions have been made that bradycardia may be of a result of structural heart changes such as left ventricular muscle mass, secondary to malnutrition(Yahalom et al, 2013). The decrease in left ventricular mass as well as a decrease in left ventricle end diastolic and end systolic dimension, stroke volume, cardiac output, and cardiac index have all been linked to patients with AN/BN. Studies suggest that a decrease in preload leads to the atrophy of the cardiac muscle itself, which may be a compensatory mechanism in the setting of chronic vascular volume depletion (Meczekalski et al, 2013). Due to the low caloric diet, the mechanism of bradycardia, as seen in anorexia patients, is thought to be mainly as a result of decreased metabolism of energy utilization and a physiological adaption to increasing vagal tone (Yahalom et al, 2013). Bradycardia is considered significant due to its association with sudden death and can be especially dangerous if seen in conjunction with other arrhythmias or ECG abnormalities; for example, prolonged QTc interval, secondary to electrolyte disturbances such as hypomagnesemia, hypokalaemia and hypophosphatemia (Yahalom et al, 2013).

Tachycardia

“QT interval is a measure of myocardial repolarization and its length is associated with life-threatening ventricular tachycardia. Thus, a prolonged QT interval is a biomarker for ventricular tachyarrhythmia and a risk factor for sudden death” (Jáuregui-Garrido; Jáuregui-Lobera, 2012). In BN patients, exertional sinus tachycardia, hypotension and orthostasis can be seen as a result of repeated episodes of induced vomiting. Hypokalaemia can be observed, and results in prolonged QTc interval which can cause significant arrhythmias. Torsades de Pointes, a specific type of ventricular tachycardia, is the most severe and can be fatal. In addition, Ipecac, a medical syrup to induce vomiting, may abused in BN patients. The active ingredient of this syrup is emetine, which can accumulate to toxic levels and result in irreversible damage to cardiac myocytes, causing severe congestive heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death (Mehler et al, 2015). Fortunately, there is evidence that bradycardia effects as a result of AN/BN may be reversed following treatment and weight restoration but refeeding should be gradual due to the risk of refeeding syndrome which can lead to cardiac arrest (Yahalom et al, 2013).

Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion (PE) is an abnormal gathering of fluid in the pericardial cavity. Because of the limited amount of space in the pericardial cavity, fluid accumulation leads to an increased intra-pericardial pressure which can negatively affect heart function. A recent study looked at the following statistics, stating that a high prevalence of PE between 15.4% and 71.4% has been found in AN/BN sufferers (Kastner et al, 2012). In a following study that they carried out, Kastner et al (2012) concluded that patients with AN had significantly more pericardial effusions than the control group, which in fact had none. In 60 (34.7%) of the anorectic cases they looked at, there were mild or moderate PE detected at admission. Within the 60 cases, the disease occurred less than 10% more often in the restricting type (AN) [50 (36.8%)] than in the binge-purge type (BN) [10 (27%)]. In all cases, the severity of the PE’s were mild and clinically silent. This was supported by another report which found that silent pericardial effusion was present in 22% to 71% of patients with AN, and the size of the PE varied between 2 and 20 mm (Mehler and Brown, 2015). Therefore, it was shown that although pericardial effusions were present, they were small or moderate and none of the patients in this case developed a cardiac tamponade, a significant pressure from the fluid build-up (Kastner et al, 2012). However, rare cases do exist in which there are reports of cardiac tamponade that required immediate treatment (Mehler and Brown, 2015). In conclusion, it is evident that there is a direct link between eating disorders and pericardial effusion. There is very little difference in the likelihood of a PE being present in either form of eating disorder, and finally, all PEs found were of moderate type, clinically silent and therefore, the majority of patients do not get to the point where the heart is unable to pump enough blood needed by the rest of the body.

Conclusion

It is clear from the abundant studies carried out on eating disorders that both Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa belong within the class of dangerous diseases. The obsessive fear of weight gain, persistent limited food intake and subsequent physiological aberrations have profound short-term and long-term consequences for the general health of the patients (Meczekalski et al, 2013). It is evident that the cardiovascular system is by far the most heavily affected and the main contributor to the frightening mortality rate associated with these disorders, especially in AN (Yahalom et al, 2013). The ECG abnormalities in particular give a graphic representation of the damage being done, but also provide a diagnostic tool to aid in the treatment for these diseases. The psychological investigations into the complex origins of AN/BN are widespread, with many crediting early trauma, familial tensions as well as pressure placed upon the individual psyche by external sources. What is clear is that eating disorders are multifaceted diseases whose origins are perhaps more difficult to treat that the actual symptoms. The far reaching pathophysiological effects of AN and BN are undeniably vast, making it a worrying fact that its prevalence continues to spread.

Bibliography

• Green, M.; Rogers, J.; Nguyen, C.; Blasko, K.; Martin, A.; Hudson, D.; Fernandez-Kong, K.; Kaza-Amlak, Z.; Thimmesch, B.; Thorne, T. (2016): Cardiac Risk and Disordered Eating: Decreased R Wave Amplitude in Women with Bulimia Nervosa and Women with Subclinical Binge/Purge Symptoms. European Eating Disorders Review 24: 455-459

• Jáuregui-Garrido, B.; Jáuregui-Lobera, I. (2012): Sudden death in eating disorders. Vascular Health and Risk Management 8: 91–98

• Kalla, A.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Garg, J.; Patel, N.C.; Figueredo, V.M. (2017): Gender and Age Differences in Cardiovascular Complications in Anorexia Nervosa Patients. International Journal of Cardiology 227: 55-57

• Kastner, S.; Salbach-Andrae, H.; Renneberg, B.; Pfeiffer, E.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Schmitz, L. (2012): Echocardiographic Findings in Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa at Beginning of Treatment and After Weight Recovery. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 21: 15-21

• Meczekalski, B.; Podfigurna-Stopa, A.; Katulski, K. (2013): Long-term Consequences of Anorexia Nervosa. Maturitas 75: 215-220

• Mehler, Philip S; Brown, Carrie (2015): Anorexia Nervosa – Medical Complications. Journal of Eating Disorders 3: (1) 11

• Padfield, G. J.; Escudero, C. A.; De Souza, A. M. Steinberg, C.; Gibbs, K. A.; Puyat, J. H.; Lam, P. Y.; Sanatani, S.; Sherwin, E.; Potts, J. E.; Sandor, G.; Krahn, A. D. (2016): Characterisation of Myocardial Repolarization Reserve in Adolescent Females with Anorexia Nervosa. Circulation 133: 557-565

• Rienecke, R. D.; Sim, L.; Lock, J.; Le Grange, D. (2016): Patterns of Expressed Emotion in Adolescent Eating Disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57: 1407-1413

• Rikani, A. A.; Choudhry, Z.; Choudhry, A. M.; Ikram, H.; Asghar, M. W.; Kajal, D.; Waheed, A.; Mobassarah, N. J. (2013): A Critique of the Literature on Etiology of Eating Disorders. Annals of Neurosciences 20: 157-161

• Tafa, M.; Cimino, S.; Ballarotto, G.; Bracaglia, F.; Bottone, C.; Cerniglia, L. (2017): Female Adolescents with Eating Disorders, Parental Psychopathological Risk and Family Functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 28-39

• Vedel-Larsen, E.; Iepsen, E. W.; Lundgren, J.; Graff, C.; Struijk, J. J.; Hansen, T.; Holst, J.J.; Madsbad, S.; Torekov, S.; Kanters, J. K. (2016): Major Rapid Weight Loss Induces Changes in Cardiac Repolarization. Journal of Electrocardiology 49: 467-472

• Walter, C.; Rottler, E.; Von Wietersheim, J.; Cuntz, U. (2105): QT-Correction Formulae and Arrhythmogenic Risk in Females with Anorexia Nervosa. International Journal of Cardiology 187: 302-303

• Wozniak, G.; Rekleiti, M.; Roupa, Z. (2012): Contribution of Social and Family Factors in Anorexia Nervosa. Health Science Journal 6: (2) 257-269

• Yahalom, M.; Spitz, M.; Sandler, L.; Heno, N.; Roguin, N.; Turgeman, Y. (2013): The Significance of Bradycardia In Anorexia Nervosa. International journal of Angiology 22: (2) 83-93