Exosomes - novel tools in diagnostics and treatments

Written by: Vujic Vesna and Volnermanis Baraks

Supervisor: Dr. Gergely Jócsák

Physiology Department, University of Veterinary Medicine, Budapest

Contents

Introduction

|

Exosomes are a subtype of extracellular vesicles that are membrane-derived, they are formed as a result of a selective intracellular process in which plasma membrane lipoproteins are placed within endosomes, later to be released into the extra cellular space. They exist and are secreted from almost all cell types in the body, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic (Johnstone, 2006).

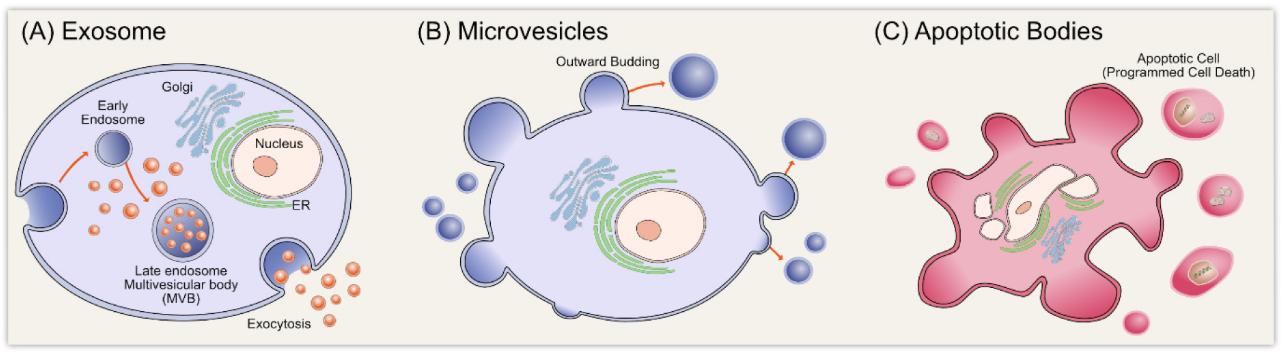

Théry et al (2002) stated that despite their similarity, exosomes differ from microvesicles in the fact that they are secreted only from living cells, whereas microvesicles can be produced from cells which have undergone apoptosis (Fig. 1). In addition, contrary to microvesicles that bud from the plasma membrane, exosomes are released from the cell following a fusion between multi vesicular bodies with the cell plasma membrane (Skotland et al, 2019).

Being part of the cellular secretome, exosomes transfer cellular constituents (DNA, mRNA, lipids, proteins) extracellularly in a paracrine fashion to a nearby cell or, alternatively in a systemic fashion - travel through the blood stream to reach a more distant cell. Exosomes possess various additional attributes, such as the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, avoid inducing any response of the immune system and withstand degradation of any enzymes (Sarko and McKinney, 2017). A recent study by Jeppesen et al (2019) has compared ‘classical exosomes’ (containing tetraspanins CD63, CD81, or CD9) and ‘non-classical exosomes’ (do not contain the mentioned tetraspanins). This study showed that ‘classical exosomes’ do not contain DNA and are not the mechanisms for active DNA release as previously believed. However, exosomes do contain RNA and RNA binding proteins.

Current research work is aimed at thoroughly understanding the way cells communicate with each other. Exosomal attributes mentioned beforehand are the reason why one of the main fields focuses at utilizing exosomes as a natural delivery vehicle system for therapeutic drugs to different cells (Sarko and McKinney, 2017).

Biogenesis

|

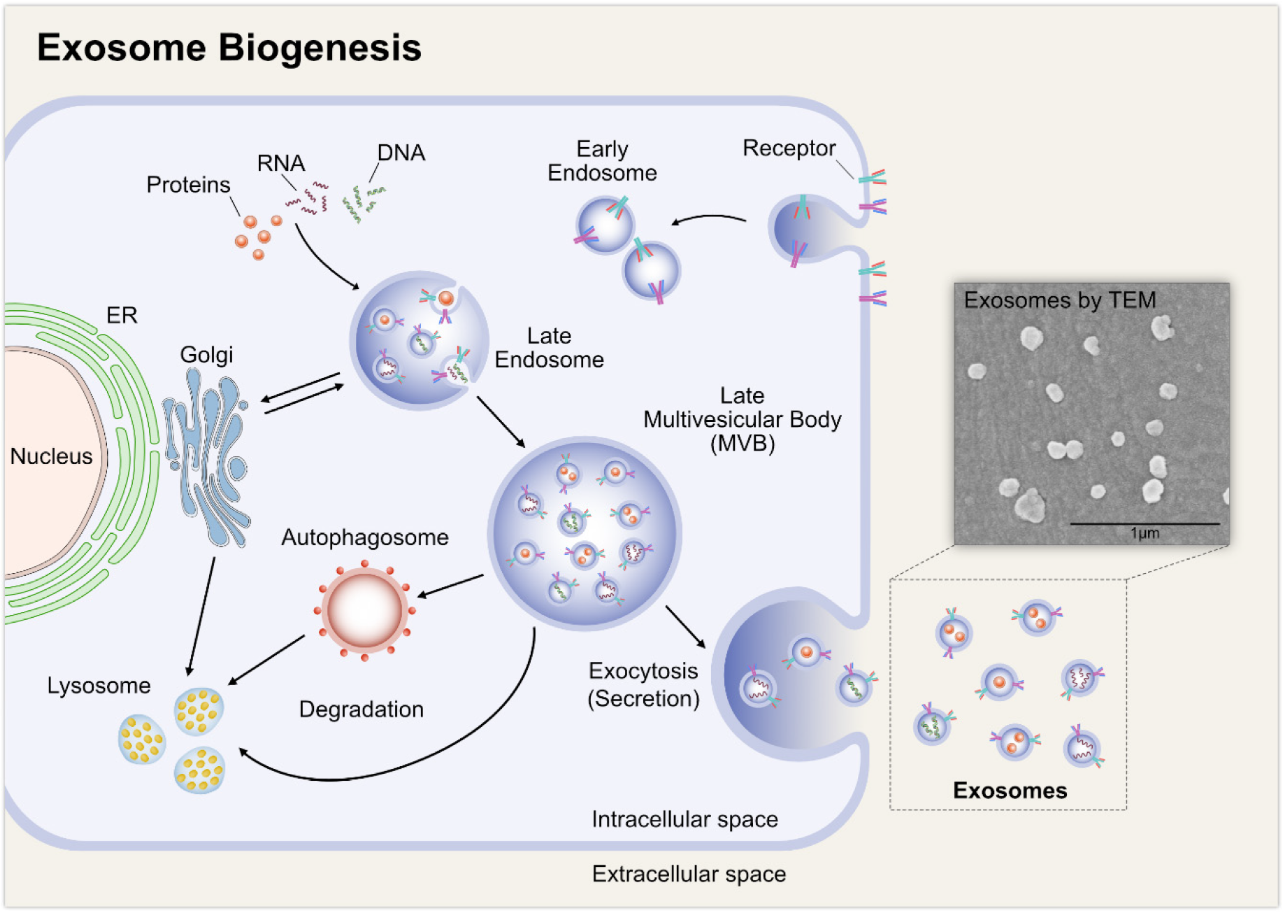

Exosomes are believed to originate from multivesicular bodies (MVB), a type of endosome that contains membrane-bound intraluminal vesicles (ILV). ILVs form inside the MVBs by budding into their lumen. As can be seen in Fig. 2, once formed, MVBs can either undergo degradation by fusing with lysosomes or be released as exosomes to the extracellular environment by fusing with the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane of the cell (Sarko and McKinney, 2017).

Henne et al (2011) showed that endosomal sorting complex transport (ESCRT) mechanism has an important role in the formation process of ILVs, facilitation of MVB formation, vesicle budding, and exosomal cargo sorting into MVBs. However, a review by Zhang et al (2019) stated that the cargo sorting process can be ESCRT-independent as well, depending on the origin of the cell type.

Structure and chemical content

Structure

Exosomes are flattened ‘saucer-like’ spheres with a lipid bi-layer exterior, ranging approximately 30-150 nm in diameter with a density of 1.13 – 1.19 g/ml (Théry et al, 2002).

Skotland et al (2019) showed that lipids have great functional importance in the biology of exosomes. Lipids are important for exosomal membrane structure and are essential for exosome formation and release to the extracellular environment as well. Exosomal lipid composition shows similarities with lipid rafts, it is rich and includes:

Chemical content

|

Nucleic acid composition of exosomes includes both DNA and RNA. Lötvall and Valadi (2019) observed that exosomal RNA contains very low amounts of ribosomal RNA, which indicates presence of other RNA types, such as mRNA. Further profile analysis of the exosomal mRNA showed genetic difference between exosomes to their parental cell. These findings indicate selectivity of exosomal RNA and in the way in which parental cells allocate a certain number of genes for exosomal delivery. In addition to RNA, exosomal DNA has been found to be genomic, containing all chromosomes (Waldenström et al, 2012);(Cai et al, 2016).

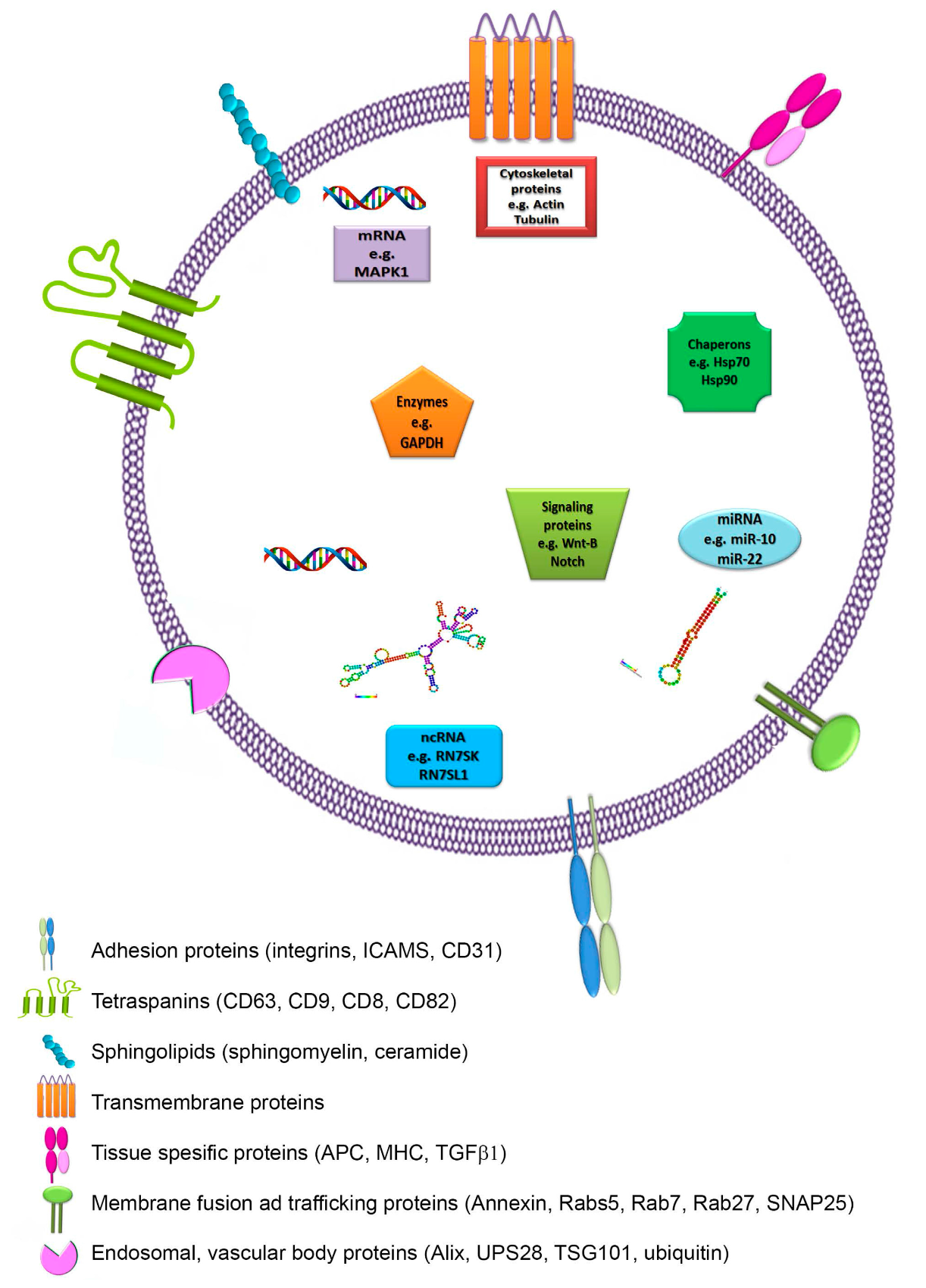

Théry et al (2002) stated that proteins currently detected in exosomes are of cytoplasmic origin, the membrane of endocytic compartments or the plasma membrane. These proteins vary based on the cell type from which the exosome has originated from. Protein composition includes (Fig. 3):

Proteins involved in intracellular membrane fusion and transport (annexins, RAB proteins)

Proteins involved in signal transduction (kinases)

Metabolic enzymes (peroxidases, pyruvate kinases, lipid kinases)

Proteins involved in organization of large molecular complexes and membrane subdomains (tetraspanin)

Cell specific transmembrane proteins (α- and β-chains of integrin, immunoglobulin family members, cell surface peptides)

Jeppesen et al (2019) showed that several of the mentioned proteins were not found in the classical tetraspanins-enriched exosomes as previously believed. The study states that further clarity regarding the protein composition of exosomes is needed.

Methods of exosome extraction

|

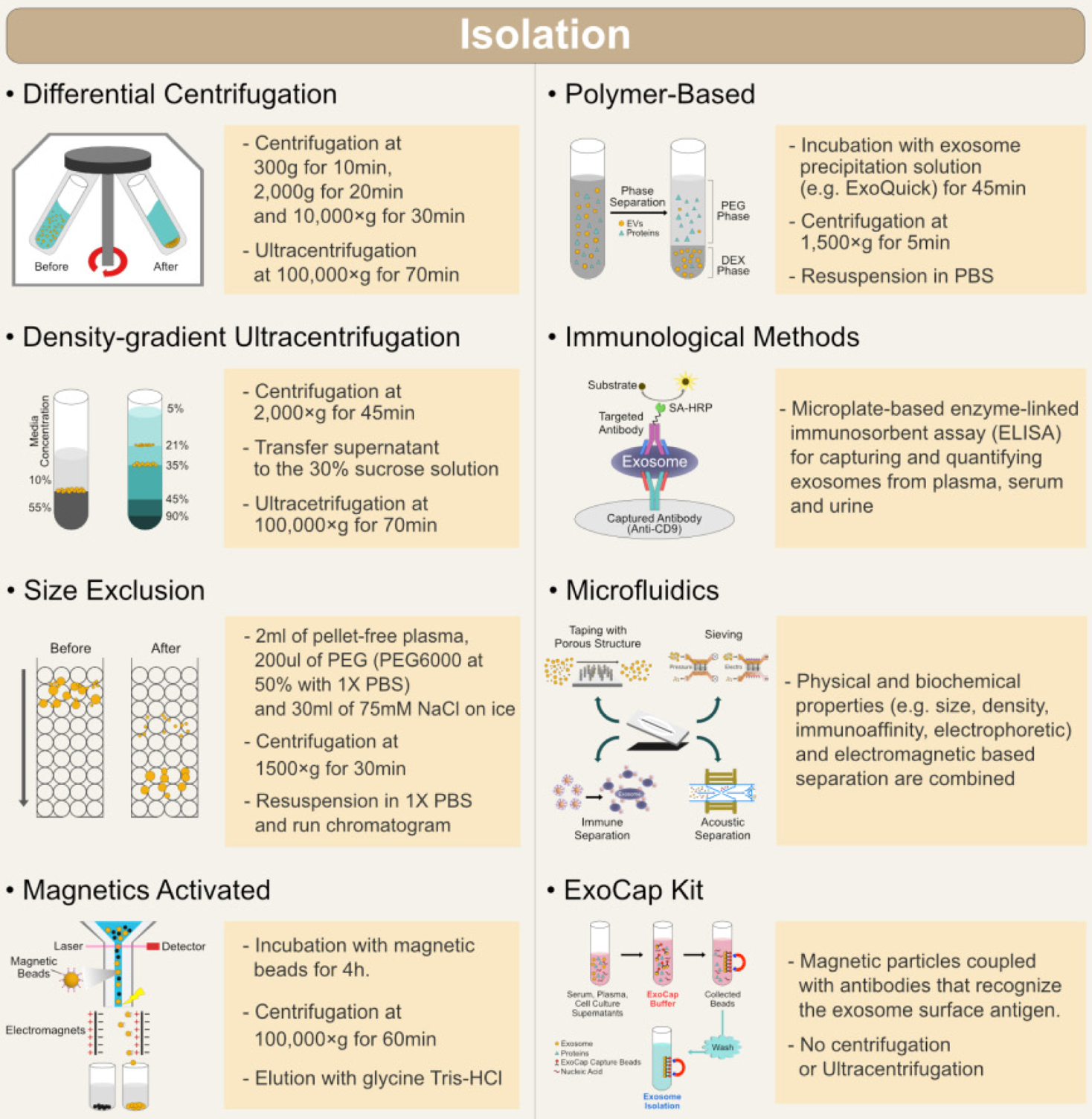

Since exosomes are very small particles, in order to study them and find out more about their potential roles and possible usages, methods for their quantitative and qualitative isolation had to be developed (Fig. 4). The developing techniques must be capable of separating exosomes from all other cellular components and from different tissue types and materials. Each technique is based on some of the characteristics of exosomes: density, size, shape, and surface proteins.

Ultracentrifugation

Ultracentrifugation (UC) is the most commonly used method of isolation. It creates high centrifugal forces which cause exosome precipitation based on their size and density. Two types of UC are used: analytical (for investigation of physicochemical properties) and preparative (for separating exosomes from similar size particles). Preparative UC can consist of differential UC and density gradient UC. Differential UC is carried out by a series of centrifugations: low-speed (for removal of cell debris) and high-speed (for removal of larger vesicles and precipitation of exosomes), since the precipitation rate depends on vesicle density (Li et al, 2017). Density gradient UC separates exosomes based on their mass, size, and density. The technique’s medium is formed usually by using sucrose solution. This method allows higher purity isolation of exosomes (Livshits et al, 2015). These methods are time consuming, require special equipment and a large volume of samples, therefore are not suitable for clinical usage.

Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration (UF) is a fast method for exosome extraction, yields pure exosomes and can be used for lower volume samples, which is very important in clinical settings. UF is based on the use of multiple filters of different size. Filters will stop larger particles like cells, their debris, and macromolecules (proteins, lipids). Multiple filters are used in order to get higher purity exosomes. During each filtration step, pressure is applied in order to wash out exosomes, which can adhere to the filter (Cheruvanky et al, 2007). It was shown that UF combined with UC gives better results in exosome isolation (Li et al, 2017). UF is faster than UC and doesn’t require special equipment, however the exosomes can be trapped in the filter and lost. The applied pressure can also lead to damage and deformation of larger exosomes.

Size-exclusion liquid chromatography

Size-exclusion liquid chromatography (SEC) is used to separate exosomes based on their size. It allows fractioning of vesicles in a column with pores of different sizes. Smaller molecules are “trapped” in pores, while larger molecules are eluted from the column first. Some of the authors proposed combining SEC with UC (Koh et al, 2018), which gave reproducible results and a high yield, but the solution was diluted and the method was deemed time-consuming (Baranyai et al, 2015).

Precipitation

The precipitation technique provides easy isolation. It is fast and doesn’t require expensive equipment. Inert polymers, like polyethylene glycol, are used for isolation. Polymers form a network around sample components and decrease their solubility. The exosome precipitate forms and is isolated using low-speed centrifugation or filtration (Zeringer et al, 2015). A disadvantage of this method is lack of specificity regarding the different types of exosomes.

Immunoaffinity techniques

Various proteins are present on the surface of exosomes and are used for their isolation because of the immunoaffinity interactions between antibodies and antigens (proteins). The challenge is choosing the proper exosome membrane protein as a marker, allowing the technique to be specific. Markers are ideally part of an exosomal membrane, and specific for different exosomes or present in a high concentration on their surface.

Antibodies are immobilized on different media (magnetic beads, microplates, chromatography matrices). Antibodies coated on magnetic beads can be used for isolation directly from body fluids, which eliminates the need for extra purification steps, like centrifugation (Zarovni et al, 2015).

Limitations of these methods include the availability of species and exosome specific antibodies, suggesting that these methods are not suitable for large scale isolation. In addition, the elution buffer used to separate exosomes from antibodies, can disrupt biological properties of vesicles, therefore some milder elution conditions must be used.

Microfluidics-based isolation techniques

Many exosome roles in normal cell life, as well as in the course of some diseases, have been discovered, causing an increasing need for more sophisticated and precise methods of their extraction. Microfluidics-based techniques use not only physical (size and density) and biochemical (immunoaffinity) properties of exosomes, but also include special sorting mechanisms (acoustic, electrophoretic, and electromagnetic).

Acoustics-based microfluidics use ultrasound to separate particles according to their size and density. Ultrasound waves apply force on particles in the solution, the strength of the force depends on the physical properties of the given particle. Particles go through a nano filter. Continuous flow is applied so the chance of clogging is minimized, and larger particles move faster (Lee et al, 2015).

This method is fast and applicable for small volume samples.

Exosomes as a diagnostic tool

Exosomes play an important role in the pathology of some diseases and can be utilised as a diagnostic tool.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers are molecules which indicate physiological processes, diseases or the response of an organism on application of a therapeutic agent. A good biomarker is specific, accessible, accurately represents current state of the organism, and easily detectable (Müller, 2012).

Exosomes are always produced in the cells, regardless of the health status of organism. If there is alteration of the parent cell, the produced exosomes will also change. Scientists are trying to use this property for development of methods to detect specific exosomes which will serve as biomarkers for some diseases. Since they can be found in all body fluids (saliva, urine, blood, semen, cerebrospinal fluid), there is an increased need for the characterisation and isolation of exosomes (Fig. 5).

Cancer diagnostics depend on biopsy. This technique has some disadvantages, which can be overcome by the usage of exosomes, such as its invasiveness, bleeding, infection, and direct damage of tissues or organs. Exosomes contain tumor-specific biomarkers (RNA, proteins, lipids), which are released in the environment of the altered cells (Waldenström et al, 2012);(Cai et al, 2016). These molecules can be transported to nearby or distant cells and promote excessive proliferation of healthy cells and their subsequent transformation into tumor cells (Al-Nedawi et al, 2008);(Melo et al, 2014). Since cancer cells require a lot of energy for rapid cell growth, they can stop glucose uptake of non-tumor cells using molecules secreted in exosomes (Fong et al, 2015). Exosomes can also influence drug resistance by transferring mediators of drug resistance (Sousa et al, 2015) whilst escaping the detection of the immune system (Miyazaki et al, 2018).

Protein content in exosomes is much larger in patients with cancer, hence why examination of certain exosomal proteins have been successfully used for detection in urine, serum and plasma exosomes (Panagiotara et al, 2017) of prostate (Øverbye et al, 2015), colorectal (Jia et al, 2017), melanoma, lung, (Sandfeld-Paulsen, 2016) and breast cancer (Huang and Deng, 2019).

Neurodegenerative diseases, like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and prion disease, are consequences of aggregation of misfolded or mutated proteins, usually transported via exosomes, which lead to the spreading of disease from cell to cell in the central nervous system. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and is characterised by plaques formed by β-amyloid peptide and tau proteins. These molecules are processed within and secreted from exosomes. Prions are infectious proteins responsible for scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle, and Creutzfeldt - Jakob disease in humans. Prions are easily transferred from cell to cell with the help of exosomes. All the proteins mentioned above have diagnostic and prognostic potential and have been successfully isolated from cerebrospinal fluid exosomes (Coleman and Hill, 2015).

Exosomes are associated with many cardiovascular diseases. These can contain chemokines, heat shock proteins and complement factors, which have an important role in the development of these diseases and can be detected. It is shown that after myocardial infarction, level of specific exosomal miRNA in blood rises, which can be used as biomarker for death of cardiomyocyte. Exosomal proteins have a role in heart transplant rejection, a characteristic which can be used for tracing acute transplant rejections (Zamani et al, 2018).

Therapeutics

|

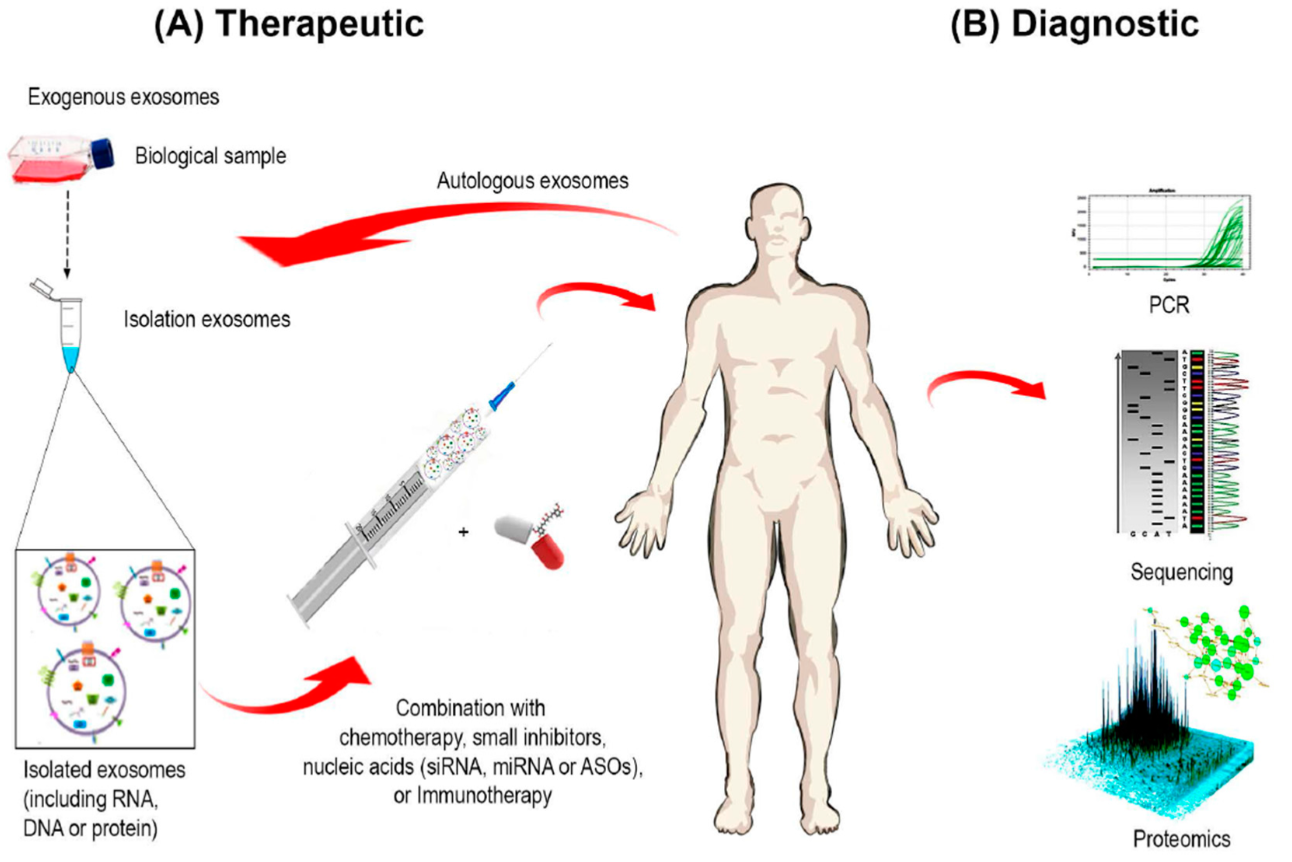

Since exosomes have many important roles in physiological and pathophysiological processes, scientists are trying to use them as potential therapeutics for vaccine development, gene therapy and drug delivery. If the content of vesicles can be modified, it could carry therapeutic agents to desired cells. Usage of exosomes offers many advantages due to the fact that they are acellular and will not replicate nor cause metastasis. They can be isolated from the patient’s own cells which will lower the possibility of being detected by the immune system (Fig. 5). The content they transport is protected from degradation until it reaches the target cell (Sarko and McKinney, 2017).

One way for prevention of metastases is blocking exosome cellular uptake, either by blocking receptors on tumor cells or healthy cells (Rak, 2013).

Classical cancer therapy is not entirely specific and often causes damage to healthy cells. It is shown that exosomes containing cytotoxic drugs prevent the accumulation of drugs in tissues which are not targets. In this way, the effect of the drug will be increased, since its concentration won’t be lowered due to increased delivery precision. Resistance to the drug can be avoided since its entrance to the cell is changed. Exosomes can cause tumor regression by oncogene inactivation and can be used as gene therapy since they have a role in horizontal gene transfer. Future research steps focus mainly on utilizing exosomes to deliver CRISPR associated genome-editing systems to tumour cells for the enhancement of precision oncology (Syn et al, 2017).

Exosomes influence the immune system by suppression and activation. This property is used for development of acellular antigens for vaccine development against infectious agents and tumors. Surfaces of exosomes can be modified in such way, which leads to antigen presentation and the activation of T cells]. This modification is achieved when dendritic cells are incubated with cancer antigens and exosomes are isolated from these cells [[#Syn.

Exosomes can cross the blood-brain barrier and be used for treatment of brain tumours and neurodegenerative diseases.

Mesenchymal stem cells are the most common source of exosomes. Exosomes derived from these cells contain molecules which can inhibit inflammation and cause regeneration in injured tissues (Syn et al, 2017) (e.g. cardiac tissue after myocardial infarction (De Toro et al, 2015)).

Reticulocytescan be infected using a malaria causing parasite. Resulting exosomes produced from these cells can be used for immunisation. Infection of dendritic cells with different microorganisms, like Streptococcus pneumoniae, offers the same possibility (De Toro et al, 2015).

Prokaryotic cells also produce exosomes. Since exosomes have a role in horizontal gene transfer, they can mediate antibiotic resistance in bacteria (Kim et al, 2015). This characteristic can be used for further studies on exosome application for inhibition of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

Although there are many research papers about exosomes, their field of research is still relatively young. If we look at all the functions of exosomes and all the possibilities they offer, it is necessary to develop techniques that will be capable to provide their quick, quantitative and qualitative isolation and characterization. Ideally, these methods should also be less expensive and available. This will provide further insight on their role and possible clinical applications. The presence of exosomes in bodily fluids opened the possibility of creating non-invasive methods for diagnostics and prognosis of many diseases. Their cell specificity gave scientists opportunities for developing disease-specific therapies and possible cure for currently untreatable diseases.

References

Articles

Patents

Figures

All the figures have been taken from open access articles