THE PHYSIOLOGY OF SLEEPWALKING

Contents

Abstract

Somnambulism is a sleep disorder that occurs in NREM sleep. It is commonly seen in children, but can in some cases appear in adult patients, although the difference between the two are significant. Unfortunately, there is little data concerning the topic, and many suggestions regarding the causes and treatment on somnambulism. Sleepwalking can have several consequences both for the affected patient and other people in the household. The misconceptions are many, especially regarding how the somnambulistic episodes take place and the following consequences. Furthermore, somnambulism can be connected to certain psychiatric diseases and psychotropics (Zadra et al, 2013). Additionally, sleepwalking can occur in patients with Tourette’s, Parkinson’s, hyperthyroidism and migraine (Mume et al, 2010). The importance of hypersynchronous delta waves during NREM sleep in somnambulistic patients has also been studied.

Physiology of sleepwalking

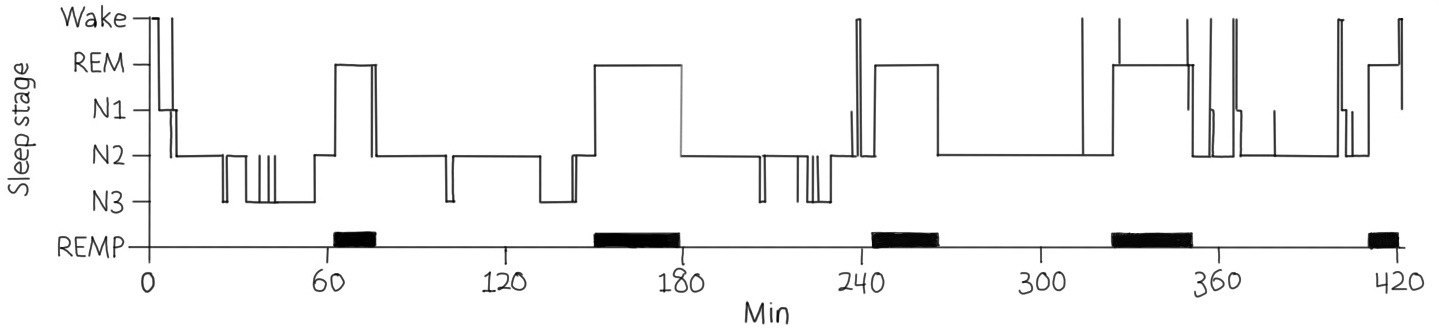

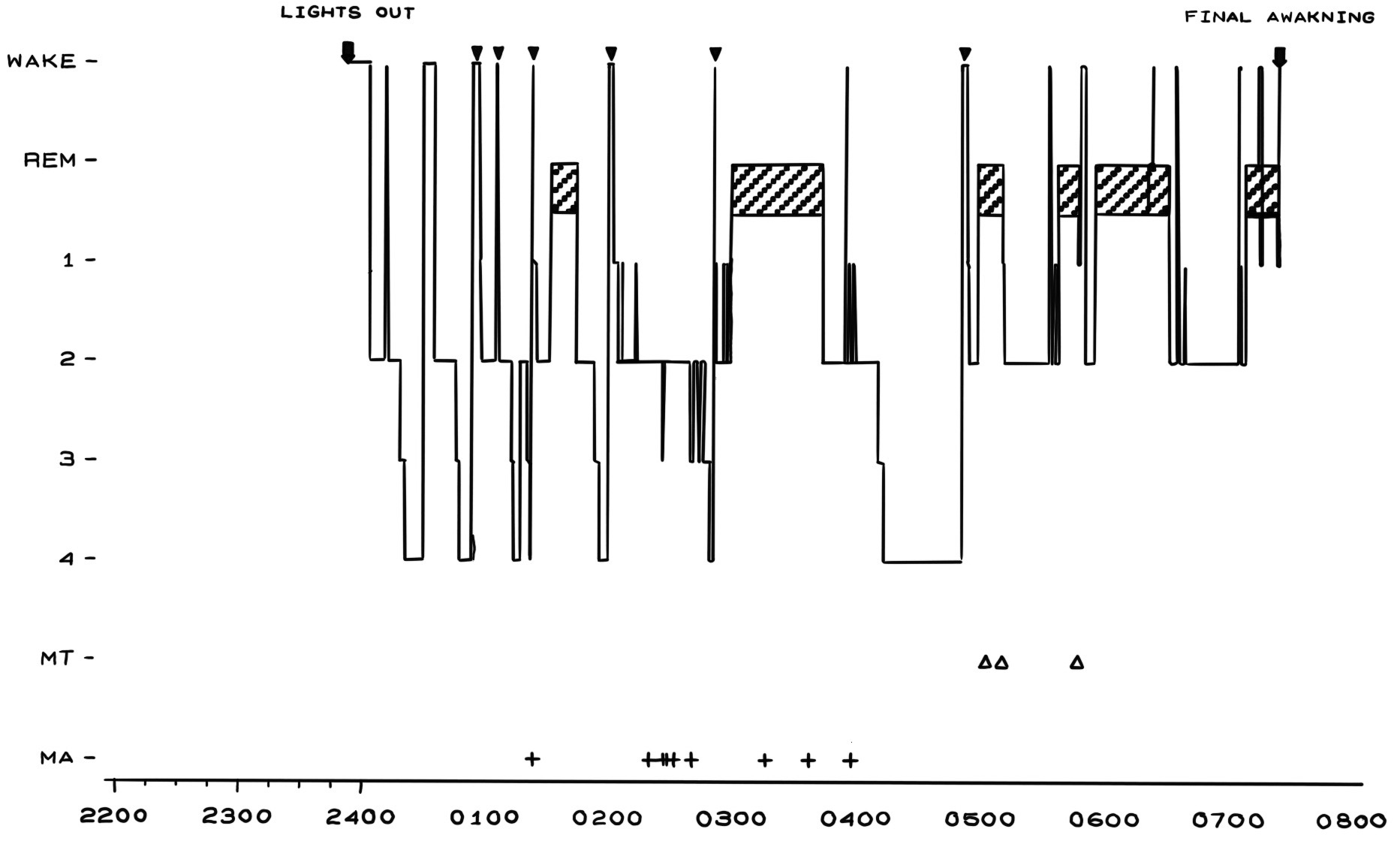

On a physiological aspect, the sleep cycle can be divided into two main parts; rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. This is based on measures like electroencephalogram (EEG), eye movement and muscle tone. NREM sleep has three further divisions: onset of sleep, light sleep and deep or slow wave sleep (SWS). A typical night of sleep is characterized by sleep cycles (see figure 1) consisting of all these stages of sleep (Zadra et al, 2013). While the sleep cycle in a person struggling with night terrors or somnambulism will show many more arousals during the night. The transitions from 4-0 stage sleep are more frequent (see figure 2).

Figure 1: Different sleep stages in a healthy person's typical night (Zadra et al, 2013).

Figure 2: A hypnogram of a patient struggling with somnambulism.

MA – minor arousal, MT – minor movement, ▼ – 0-4 transitions (Crisp, 1996)

REM and NREM sleep will alternate throughout the night, but NREM sleep typically occurs during the first third of the sleep cycle. REM is usually prominent during the last third. It is during NREM sleep that episodes of somnambulism usually happen (Zadra et al, 2013).

In children movements in a somnambulistic episode are rather simple, like walking around, small hand movements or other small gestures. However, in adults, a more complex motor control can be seen (Zadra et al, 2013).

There is no evidence that somnambulism in adults is related to neuropathological disorders. However, in patients over the age of 50, REM sleep behavior disorder can be seen in the case of development of neurodegenerative processes such as Parkinson’s disease or dementia (Zadra et al, 2013).

Sleep walking among children

Sleepwalking is common among children. It is usually harmless for the child, although in some cases it may cause danger for the individual or to others as well, but this is less likely. A review has shown that 5 % of all children sleepwalk (Stallman et al, 2017). Night terrors and sleep talking are often discussed together with somnambulism. Commonly discussed causes of somnambulism in children are insufficient sleep, sleep fragmentation and increased need for sleep. Sleepwalking among children is often associated with several sleep disorders. This includes confusing arousals, sleep disordered breathing, sleep talking and rhythmic movement disorders (Heussler, 2005).

Daytime functioning

Children who are affected by somnambulism and other sleep disorders are often exposed for more behavioral problems such as anxiety, anger or other emotional problems. Activity during the day is referred to as daytime functioning. It is not known whether daytime functioning has a direct or secondary function on sleepwalking compared to other factors associated with sleepwalking. However, in adults it is proven that there is a relationship between sleepwalking and daytime functioning. This includes other factors such as fatigue (Heussler, 2005). This has not yet been further investigated in children (Stallman et al, 2017).

Sleep Schedule

There are many factors that may affect sleep disorders, however, they are not entirely understood. Having a good sleep schedule is proven to be important. Having a poor sleep routine is common for children who sleepwalk. This includes not sleeping enough and having a less stable NREM sleep cycle (Stallman et al, 2017). Following this, it is recommended that one ensures a stable sleep routine and maintain maximal sleep for the child. It is important to distinguish between daytime sleepiness and sleep fatigue. A child who falls asleep in certain positions or situations, such as to loud music or on a parent’s lap, will not be in the same situation as a child who feels tired and relies on naps during the day. Generally, the lack of sleep advances from insufficient sleep, sleep fragmentation and primarily the increased need for sleep (Heussler, 2005).

It is proven that children with unstable sleep routines also have more daytime behavioral issues. Another factor that affects behavioral issues, is sleep length. However, a stable sleep routine may prevent daytime behavioral issues more than the same amount of sleeping hours every day can, because the quality of sleep depends on the time the child goes to bed. This suggests that sleep routine is more important than the length to get a better daytime behavior (Stallman et al, 2017).

It is important to understand somnambulism according to the age of the children, since there might be a link between sleep and daytime problems. It is reported that children at the age of 6-11 years demonstrate that sleepwalking was not a risk for daytime sleepiness, although it was linked to other parasomnias parallel with daytime sleepiness. This may demonstrate that daytime functioning has an indirect function on sleep disorders (Stallman et al, 2017).

Suggested Cause of Somnambulism: Serotonergic Systems

We do not know much about the physiological reason behind sleep walking. Although, there are many hypotheses; one of them discussing the serotonergic system playing a role and possibly differentiate the reason behind sleepwalking in children and adults.

The etiology of sleepwalking is not well understood. Physiological, genetic, developmental and physiological factors are some of many factors that have been suggested as a cause for somnambulism. Although, it is known that it can be triggered by fever, drugs, stress and big life events. Serotonin also shows a link between fever and sleepwalking (Juszczak and Swiergiel, 2005). Another factor that can cause somnambulism is migraine. Based on studies there is a high correlation between children with migraine and somnambulistic episodes during childhood. Somnambulism can be considered a significant clinical parameter in migraine diagnosis in children (Barabas et al, 1983).

A report (Juszczak and Swiergiel, 2005) states that serotonin facilitates the motor movement and therefore exerts an effect on the motor neurons. This may activate and facilitate some spinal motor reflexes. The serotonin is located in cell bodies in different nuclei near the brain stem. It is also demonstrated that serotonergic neurons recognize the CO2 level in blood and therefore corresponds to hypercapnic acidosis.

It is known that somnambulism is most common in children. The occurrence increases to the age of ten, before it will decrease rapidly during adolescence. According to this hypothesis this might correlate to the maturation of the brain (Juszczak and Swiergiel, 2005).

Consequence of Somnambulism

The most prominent consequence of a child struggling with somnambulism is how it interferes with the circadian rhythm. The circadian rhythm is a part of the hypothalamus and has a regulating function. It is highly dependent on the light-dark cycles and therefore also the sleep schedule. Children who have developmental disorders might need supplements of melatonin and a good sleeping schedule. Melatonin has proven to be beneficial when adjusting the sleep phases for both children and adults. It is helpful for children affected by autism or developmental issues to assure a better sleep hygiene (Heussler, 2005).

Somnambulism in adults

In the UK 2.5% of the adult population suffer from adult somnambulism, this is close to one third of a million. (Guilleminault et al, 2005). The occurrence of somnambulism in adults is much rarer than somnambulism in children. The existence of somnambulism in children often increases to the age of 10-12 before it decreases during adolescence. Most people will outgrow the parasomnia disorder, however a percentage of 2-4% will continue experiencing somnambulism in adult life. It is unclear why some people outgrow somnambulism, and why other don’t. It is more likely that people that experienced childhood sleepwalking will experience sleepwalking in adult life as well, than that people will develop somnambulism in adulthood. Never the less, this can happen sporadically (Zadra et al, 2013).

While sleepwalking in children often is more temporal and harmless, sleepwalking in adults can often lead to injury and has a harm potential. This include that the sleepwalker might place himself or herself in dangerous or harmful situations, it can be harming bedpartner or other people close by, severe injury of sleepwalker and destruction of surroundings. Somnambulism is one of the major causes that is associated with injuries or violent behavior after an arousal from sleep. Most people that experience injuries or aggressive behavior during sleepwalking will seek clinical help (Zadra et al, 2013).

Misconceptions

There are some misconceptions about sleep walking. One misconception is that somnambulistic episodes will not affect the person during daytime. There is a study that shows that sleepwalkers can experience daytime somnolence even after nights free of somnambulistic episodes. Sleepwalkers have a much lower average sleep onset latency. Additionally, it is proven that the sleepwalker patients score higher than healthy controls on the Epworth sleepiness scale. The Epworth sleepiness scale measures the level of sleepiness during daytime (Johns, 1991). Another misconception is that sleepwalkers experience total amnesia during somnambulistic episodes. This might be true for child sleepwalkers as somnambulistic episodes in kids are thought to be more automatic behaviors and usually cause complete amnesia. However, studies have shown that adult sleepwalkers can recall specific elements of their episodes. After awakenings they can recall specific feelings, specific behaviors, actual environments and parts of episodes. A reason for this is that during episodes of somnambulism the eyes are open, and therefore environment can be retrieved by the brain (Zadra et al, 2013).

Treatments

When seeking treatment for somnambulism there are three different treatments that are recommended. These are hypnosis, scheduled awakenings and drugs. During hypnosis the subject is in an altered state of consciousness. In a study done by Flinders University, the subjects where thought self-hypnosis and reported “very much or much improvement” or “achieved substantial benefit” (Harris, M. & Grunstein R.R., 2009). While hypnosis is used in both childhood and adult somnambulism, are scheduled awakenings and drugs mainly used for kids and adults respectively. Drugs are an option when the behavior during the somnambulistic episodes are dangerous or troublesome for the sleepwalker, bedpartner or other household members. As adult somnambulism is more likely to be dangerous or aggressive, drugs are mostly given to adults. The drug used are benzodiazepines, especially clonazepam and diazepam. These drugs reduce the arousal and anxiety and quench slow wave sleep, but they may not always fully control sleepwalking. The clinicians, when giving a treatment, has to clearly state that a regular sleeping pattern and good sleeping habits, stress management and avoidance of sleep deprivation is extremely important. Another factor which is important to take into consideration when clinicians recommend treatments is the psychiatric history and medication of the patient. Somnambulistic episodes have been recognized in patients with psychiatric disorders and those who are given psychotropics. This includes sedatives, antihistamines, antidepressants, hypnotics, lithium, neuroleptics, and stimulants. It is believed that these disorder and drugs ease the regional dissociation, leading to somnambulistic events. For adults, as well as children, stress and anxiety might increase the risk of sleepwalking for people that are predisposition to somnambulism (Zadra et al, 2013).

The cause of somnambulism

Somnambulism is commonly classified as a disorder of arousal, but several clinical findings and experiments has found that it might be connected to a dysfunction in SWS regulation. Here it is suggested that the actual cause of somnambulism is that there are intrinsic abnormalities present in the slow wave sleep. One noticeable difference between sleepwalkers and the healthy control is the absence of continuous NREM sleep. Sleepwalkers have significantly more hypersynchronous delta waves (HSD) during NREM sleep than that of the control group (Zadra et al, 2013).

Hypersynchronous Delta Waves

HSD are described as continuous high voltage delta waves, present during slow wave sleep or right before a sleepwalking event (Pilon et al, 2006). Jacobsen et al noted these activities prior to a sleepwalking episode, but later studies show mixed results in the case of adult patients, with HSD being occasionally, often, or always related to sleepwalking episodes or night terrors (Pilon et al, 2006).

To help settle this disputation a new study collected data to thoroughly evaluate HSD during non-REM sleep. The results would be a comparison between somnambulistic patients and a control group, and would be recorded during normal sleep, following a 38-hour sleep deprivation period – as sleep deprivation has a known effect of increasing the frequency of somnambulistic episodes (Pilon et al, 2006).

The most prominent results were that HSD in fact did occur more often in sleepwalkers sleep EEG than in the control subjects. Another salient finding was that during stage four of the sleep cycle, there is an increase in HSD in the case of sleep deprivation. This is true for both the control group and the sleepwalkers. On the contrary, there is no evidence that somnambulistic episodes lead to an escalation in HSD or anything related to HSD (Pilon et al, 2006).

The onset of episodes seems to be affected by a sudden change in high amplitude slow oscillations. This may show cortical reactions to brain activation (Zadra et al, 2013). In a healthy person, sleep deprivation will lead to rebound of slow wave sleep and generates a more solid NREM sleep, as a response to disturbance in the body’s equilibrium between sleep and wakefulness. This physiological response seems to be absent in sleepwalkers. In their case, the response to sleep deprivation seems to be more awakenings from slow wave sleep during recovery sleep. This special response to sleep deprivation seems to be confined to slow wave sleep (Zadra et al, 2013).

Summary

To summarize, we can point out the considerable difference between child and adult somnambulism. Children has a simpler motor control than what can be seen in adults. The sleep quality plays an important role in the degree of somnambulistic episodes playing out in children. Moreover, the younger generation will experience a total amnesia after a somnambulistic episode, but adults can in many cases recall elements from the episode. Furthermore, due to more aggressive behavior and injurious episodes, drugs are more commonly used in adults than in children. As research shows, hypersynchronous delta waves can be seen in patients experiencing sleepwalking episodes on a larger scale than healthy individuals. Contrarily, there is no evidence that the buildup in HSD is connected to episodes of somnambulism.

Literature:

Barabas, G., Ferrari, M., and Matthews, W. S. (1983): Childhood migraine and somnambulism. Neurology. 33: (7) 948-948

Crisp, A. H. (1996): The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgraduate Medical Journal: 72: (852) 599-604.

Guilleminault, C.; Kirisoglu, C.; Bao, G.; Arias, V.; Chan, A.; and Li, K. K. (2005, April 07): Adult chronic sleepwalking and its treatment based on polysomnography. Brain. 128 (5) 1062-9

Harris, M. and Grunstein R.R., (2009): “Treatments for Somnambulism in Adults: Assessing the Evidence.” Sleep Medicine Reviews 13: (4) 295–297.,

Heussler, H. S. (2005, May 02): 9. Common causes of sleep disruption and daytime sleepiness: Childhood sleep disorders II. Med J Aust. 182 (9) 484-9.

Johns, M. W. (1991): A New Method for Measuring Daytime Sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep: 14: (6) 540.

Juszczak, G. R., and Swiergiel, A. H. (2005): Serotonergic hypothesis of sleepwalking. Medical Hypotheses: 64: (1) 28-32.

Mume, Co. “Prevalence of Sleepwalking in an Adult Population.” (2010, January): Libyan Journal of Medicine 5: (1) 2143.

Pilon, M.; Zadra, A.; Joncas, S.; and Montplaisir, J. (2006): Hypersynchronous Delta Waves and Somnambulism: Brain Topography and Effect of Sleep Deprivation. Sleep: 29: (1) 77-84.

Stallman, H. M.; Kohler, M. J.; Biggs, S. N.; Lushington, K.; and Kennedy, D. (2017): Childhood Sleepwalking and Its Relationship to Daytime and Sleep Related Behaviors. Sleep and Hypnosis - International Journal 19 (3) 61-69.

Zadra, A.; Desautels, A.; Petit, D.; and Montplaisir, J. (March 2013): Somnambulism: Clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. The Lancet Neurology: 12: (3) 285-294.

Figures:

Self-drawn figure 1:

Zadra, A.; Desautels, A.; Petit, D.; and Montplaisir, J. (March 2013): Somnambulism: Clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. The Lancet Neurology: 12: (3) 285-294.

Self-drawn figure 2:

Crisp, A. H. (1996): The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgraduate Medical Journal: 72: (852) 599-604.